“How quickly can we get guys back from injury? How long until they are back up to full speed? You’re not guessing, it’s data-based and numbers-based, and the more we can use this information, the smarter decisions we can make and the healthier decisions we can make,” Cahill said.

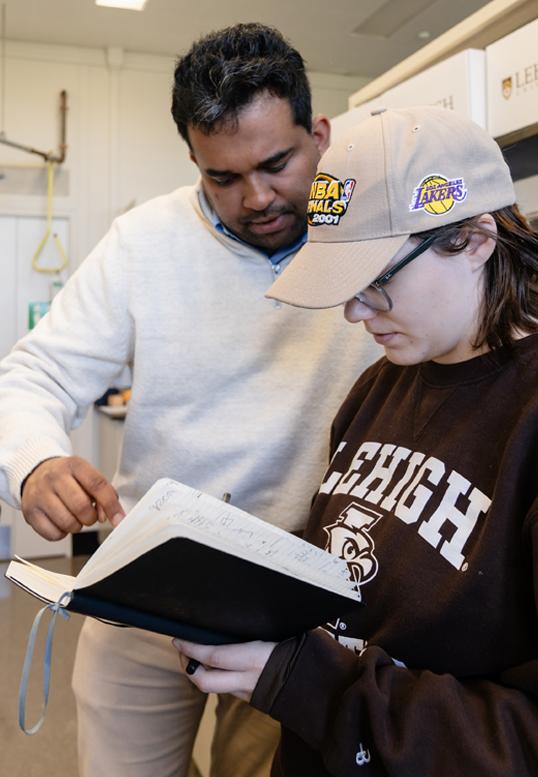

Seshadri said his team is conducting one of the few studies looking at muscle-oxygen saturation as a biomarker, or guide, to rehabilitating athletes following ACL reconstruction. Seshadri is also co-leading a similar study with the NFL’s Cleveland Browns, funded by a grant he received in 2022 from the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine.

“If we start to collect more data, we can then help forecast and assess if the athlete is on track in their healing at various time points,” Seshadri said. “What testing should be done at various time points to ensure athletes are returning at their highest level and doing what they love to do on a daily basis?”

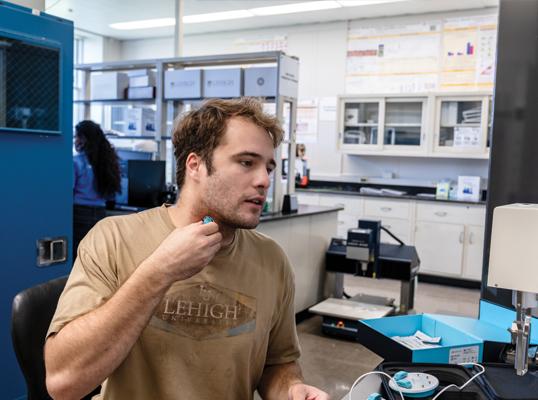

Cahill said that before wearable tech was widely available, coaches determined how to practice by viewing athletes on the field and taking an educated guess about what condition they were in. With data, coaches can now get baseline readings. Stats are collected before the season, mid-season and postseason to show how athletes are performing over time, Cahill said. If data shows their performance is lagging, coaches can determine why and potentially pull back on training to prevent injury.

The information also helps direct the kind of training athletes need. Athletes are susceptible to injuries, such as ACL tears, when their quad muscles are overtrained compared to their hamstrings, or one leg is stronger than the other, Cahill said.

“It’s really all-encompassing what you’re doing in the weight room. Are you strengthening the quad enough? Is the hamstring too strong or not strong enough?” he said. “There are a lot of different variables we are trying to track, but that’s what wearable tech has helped us to do.”

Lauren Calabrese ’07 took over as women’s head soccer coach in 2022. She was a four-year starter during her time as a student-athlete on the soccer team and said there wasn’t any hard data back then.

When Calabrese began coaching, she pushed for every women’s soccer player to be outfitted with a WHOOP, a wristband that looks similar to an Apple Watch and collects round-the-clock data such as sleep patterns, blood-oxygen levels, resting heart rate and skin temperature.