Recovering history, reviving culture

Berrisford Boothe’s goal, in his collaboration with real estate developer Jim Petrucci, is to collect “master works that define humanity, that show characters in their full, most authentic human moments.”

Berrisford Boothe was previewing his first major art auction when he struck tarnished gold. Boothe couldn’t wait to bid on a portfolio of prints by African-American artists gathered by Romare Bearden (1911-88), an influential artist and philanthropist. But he worried that its value had been diluted by moisture damage and ink-transfer staining.

Boothe, professor of art, went to a restroom to place a discreet call to his auction lifeline. Lewis Tanner Moore, a respected curator and broker, assured him the stained prints could be restored safely. He also told Boothe that he couldn’t afford not to bid on the Bearden portfolio, which had been printed by Robert Blackburn, the veteran owner of a vaunted workshop.

Armed with Moore’s advice, Boothe bought the portfolio for a fair price, outbidding rivals he thinks were scared off by the moisture damage. After having the stained prints conserved, he added the Bearden portfolio to a collection of nearly 200 works by African-American artists that he’s been building for three years and nearly 20,000 miles.

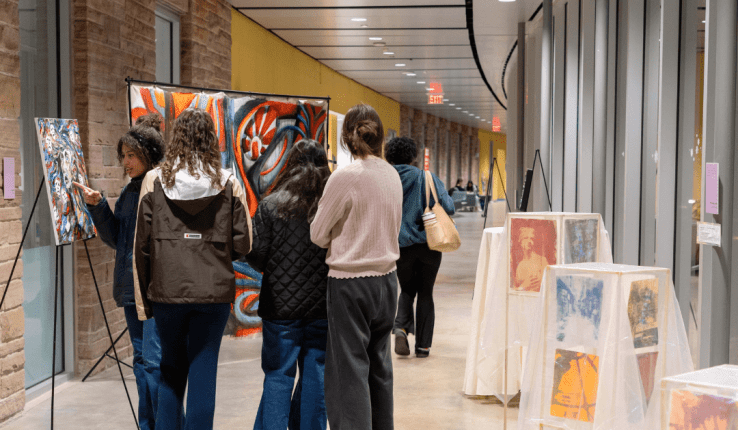

Boothe’s patron is his longtime friend Jim Petrucci, a prominent developer of commercial and industrial properties in New Jersey and the Lehigh Valley. Together, they’ve assembled a remarkably diverse, balanced group of objects by black pioneers, outsiders and revolutionaries. Last year the Petrucci Family Foundation collection was presented at three institutions, including the African American Museum in Philadelphia. A fourth exhibit is scheduled to open in November in Portland, Ore., a hotbed of racial conflict and resolution.

Started as an investment, the Petrucci collection has blossomed into an educational, ethical mission. A white man from New Jersey and a black man from Jamaica are displaying a rainbow coalition of works by people of color to debate everything from aesthetics to politics while serving everyone from at-risk youngsters to at-risk elderly artists.

“We’re using themes inside the African-American experience to foster cross-cultural understanding and reconciliation,” says Boothe. “We’re not trying to embarrass anyone about their lack of knowledge of black culture. We’re leaving the door open for them to write their own narrative. We’re prompting them to ask: How can we protect these cultural assets? Who else did our common history forget?”

The Boothe-Petrucci project began in June 2012 in Montreal. Petrucci was visiting galleries with one of his four children when he decided he wanted to start investing in art. The decision was less an epiphany than a natural evolution. At Princeton University, where he majored in American history and was a second-team all-Ivy League defensive tackle, Petrucci wrote a senior thesis on white and black patronage during the Harlem Renaissance, the cultural renaissance that flourished in upper Manhattan in the upper 20th century.

“I don’t think you can really understand American history if you don’t understand African-American history,” says Petrucci, whose family foundation supports black students. “If people can’t try to walk in each other’s shoes, we’re going to continue to slide backwards.”

To help him invest in art, Petrucci turned to Boothe, a restless aesthetic experimenter and relentless networker. Over 30 years Boothe has been an abstract painter, a realist printmaker, an abstract/realist photographer, an installation artist and a collaborator with improvisational musicians. He’s taught African-American art and co-founded Lehigh’s Africana Studies program. Last year he celebrated the university’s 150th anniversary by producing a performance by graffiti artists.

Boothe has relied on veteran collection builders to help him build his first major collection. His guru is Lewis Tanner Moore, who as a high schooler organized an exhibit of works by black artists not represented in books by white art historians. The child of an art-collecting lawyer, Moore lives with his wife in a 19th-century mansion bursting with art objects and artifacts by African-Americans and Africans. The salon/museum includes paintings by his great-uncle Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), the first internationally famous African-American artist.

Moore has served as Boothe’s scout, sounding board and cultural sage. Boothe has internalized Moore’s colorful sayings about collecting economically (“You buy the object, not the store”), ergonomically (“Every collection has a point of view; every collection has the flow of a river”) and emotionally (“It’s not about the value of your collection; it’s about the quality of the characters you collect”).

Following Moore’s lead, Boothe has built a collection revolving around African-American identity, history and even sexuality. Hale Woodruff’s “Coming Home,” a Cubist/realist linoleum cut, represents a return to the American South from 1920s Paris, where expatriate black artists co-existed with Picasso and other Cubists. Calvin Burnett’s ink drawing “Man Shortage” depicts women dancing together while their men are off fighting World War II. Kara Walker addresses injustice in a silhouette of a black woman shouldering a larger silhouette of a white grand dame.

Boothe served as Petrucci’s guide during a 2014 sale at Swann Auction Galleries in Manhattan, a relatively new leader in the booming market for fine art by African-Americans. Shepherded over the phone by Boothe, Petrucci paid nearly double the top estimate for “Wandering Boy,” Dox Thrash’s 1940 watercolor of a muscular young man in a white hat and a loose white shirt, sitting with a pensive, powerful gaze. In the process he set an auction record for a Thrash watercolor.

Petrucci paid a high price because he believes “Wandering Boy” has a high emotional value. He plans to use the portrait as an inspirational visual model for annual tributes he underwrites for varsity football players and 12 top students at a troubled high school in Irvington, N.J. He launched the event 15 years ago after reading a New York Times story about a football player shot dead in front of the school.

“There’s something about the gaze of the wandering boy, or man, that tells me he’s wondering what the future will bring,” says Petrucci. “All young people are concerned and anxious about what the future will bring. We’re all staring into a pretty big world; we’re all wanderers and wonderers.”

The partnership between Boothe and Petrucci has stretched their relationship. Petrucci has taught Boothe about the business world’s tight deadlines and budgets. Boothe has taught Petrucci about the art world’s more elastic values, aesthetic and financial. Both men have learned a lot about the auction world’s roller-coaster rides.

Petrucci and Boothe insist their friendship has never been threatened by debates over finances or personal tastes, two divisive forces. “We’re very forthright with one another, which makes for easy communication,” says Petrucci. “Berris suffers no fools, which I appreciate. In that way, we’re cut from the same cloth.”

Boothe: “The first sign that our partnership threatens our friendship, I quit.”

Petrucci: “Perhaps we’re setting an example for mutual understanding.”

Boothe admits he’s been enlightened, and exhausted, by driving tens of thousands of miles to visit auction houses, galleries, museums, studios and dealers’ homes. This calendar year he plans to spend more time making art, and building an international audience for his art, during a two-semester sabbatical from teaching at Lehigh. At the same time he’ll continue his quest to help young professionals archive the careers and lives of established, elderly, overlooked black artists, so they can “work more and worry less about their legacy.”

“We’re dealing with a country with a massive trove of negative imagery of African-Americans,” says Boothe. “What we’re offering here are corrective, positive images that sometimes address long-standing negative perceptions and ignorance. We don’t want to collect pretty pictures that just whitewash black life. We want to collect master works that define humanity, that show characters in their full, most authentic human moments.”

by Geoff Gehman ’89 M.A.

Photos by Ryan Hulvat

Posted on: