Naylor took great care in responding to correspondence, which shaped the team’s responsive approach to the Archive, says Foltz. “That is part of the ethos [of this project]. From the beginning, [we] have really talked about how the archives can give us a sense—and, of course, we cannot know entirely what Naylor would want—but a sense in terms of how she collected materials, how she cared for them, how she organized them.”

Part of that approach included a sensitivity to the humanity behind the documents. Processing the correspondence, says Edwards, was “incredibly labor intensive” and took three quarters of the past three years to complete, due in part to the appearance of many individuals within the documents. These ranged from other celebrated authors such as Toni Morrison, Nikki Giovanni, Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Julia Alvarez, to fans offering their thoughts on Naylor’s work. With assistance from Lehigh Special Collections, the team documented every name referenced in the materials, regardless of stature.

Archival processing is “intellectual work that has complex ethical questions, complex conceptual questions,” Edwards says. For example, the team collected, when possible, all names referenced in the archive, but did not make that record publicly searchable in an effort to protect the privacy of those who wrote letters to Naylor.

“[It] might seem to most people like it would be simple to make these decisions,” says Edwards. “But any kind of decision about the information you record and the information you leave out is both a conceptual and an ethical concern that has a deep history of racism and sexism in the history of knowledge.”

She acknowledges that responsiveness can only go so far, and thus requires “radical humility”: “There's a lot we don't know, a lot we can't know. Even with this incredible abundance of material, we need to be circumspect and mindful about what remains unknowable, and to really leave space for that.”

Broad Accessibility

In addition to offering access to the digital archive, the comprehensive Naylor Archive website includes resources such as information about Naylor’s life and works, a finding aid to assist scholars in connecting the collection to their own research, a blog for public-facing scholarship, a bibliography and information about related archives.

“It’s meant to be accessible,” says Foltz.

The project has resulted in several presentations and publications, including one in 2019 by Edwards and Trudier Harris of the University of Alabama. “Gloria Naylor’s ‘Sapphira Wade’: An Unfinished Manuscript from the Archive," which appeared in African American Review, explores Naylor's unfinished final work. Edwards also published “‘Burn all he has, but keep his books’: Gloria Naylor and the Proper Objects of Feminist Chaucer Studies” in The Chaucer Review in 2019. The project was recently showcased by The Recovery Hub for American Women Writers.

The team also developed a variety of engaging events and programs to connect Naylor scholars and welcome a broad audience to interact with Naylor’s writings. An April 2021 virtual event with Black Women Radicals, a public-facing platform that profiles the lives and work of Black women radicals, featured a panel discussion about the archive. Edwards and Foltz taught courses based on archive materials, and led a yearlong faculty seminar focused on the Naylor Archive that brought together Lehigh faculty across disciplines to read and discuss Naylor’s work.

Among the participants were Mark Wonsidler, curator of exhibitions and collections for the Lehigh University Art Galleries (LUAG); Kashi Johnson, chair and professor of theatre; and Melpomene Katakalos, associate professor of theatre, each of whom would contribute to the project in a unique way.

Wonsidler describes the group’s early collaboration as an “immersion in Gloria Naylor’s work… We wanted Gloria Naylor’s voice to come forward.”

He led the team in curating “Gloria Naylor: Other Places,” a physical and digital exhibition that ran from Sept. 1, 2021 through May 27, 2022. Inspired by the BBC podcast “A History of the World in 100 Objects,” the exhibition featured select objects from the Naylor Archive, each telling a different part of Naylor’s story. The “other place,” Wonsidler explains, is a location in the novel Mama Day to which the title character goes to connect with her ancestors and mystical power. The notion of place, the team noticed, was prevalent in both Naylor’s writing and in the archive itself.

“This idea of place became a really important frame for us in the process of trying to choose the key objects, bits of ephemera or manuscripts or notebooks or photographs or souvenirs from those different sites that would help to tell the story,” Wonsidler says. “So using the frame of the sequence of places, we try to weave Gloria Naylor’s story through that. … We're able to unfold that story across these different locations.”

Given Naylor’s tendency to reference music in her writing, a Spotify playlist accompanied the exhibition. A variety of programs invited the broader public to explore the exhibition and discover how art, writing and storytelling connect.

“We don't always have the opportunity to do an art exhibition about a writer,” says Wonsidler. “So I think that was exciting for us, being able to show that kind of expanded definition of what artistic production looks like.”

The Gloria Naylor in the Archives Symposium, held virtually and on Lehigh’s campus in November 2021, welcomed Naylor scholars from across the United States to “explore new directions in Naylor scholarship and/or consider how recently accessible archival materials open up new avenues for understanding Naylor’s published work and unpublished plays, screenplays [and] correspondence.” The three-day event included presentations, panel and roundtable discussions, and a keynote lecture by Maxine Montgomery of Florida State University. The symposium was by design a low-cost and accessible event, with minimal registration fees to ensure that any interested faculty, staff, student or community member could attend.

The symposium also featured theatrical readings of two Naylor plays, Candy and M’Dear, performed by Lehigh students; produced by Katakalos and directed by Johnson. Presenting these works in this manner, Katakalos says, placed the focus on Naylor’s words and allowed for broad participation.

“Plays are meant to be read out loud or performed,” she says. “They’re alive. … From a producing standpoint, it was about making sure that [Naylor’s] words were heard really vividly and really celebrating that by making it come alive.”

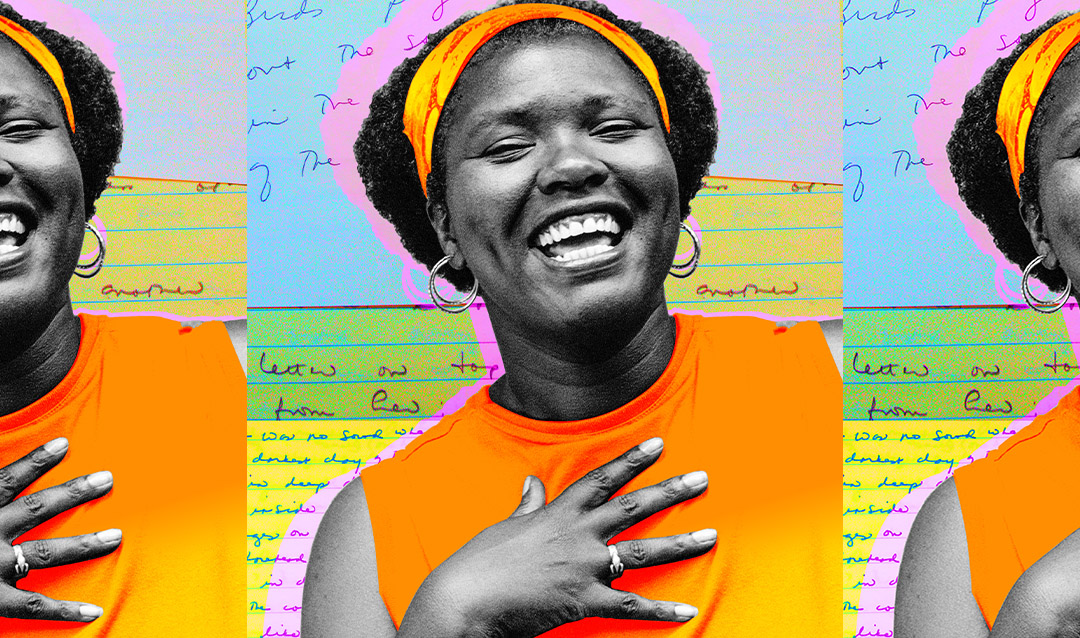

Johnson describes the experience of participating in the project: “It was joyful to experience Lehigh engage, promote, create and reassemble such beautifully vivid work. … a true testament of our love and support for Ms. Naylor and her work.”

Says Edwards: “What is really critical to this is the different ways of thinking and the conversations and the way those conversations expose new ways of looking at the materials and what's valuable or interesting or exciting about them. Everybody sees something different.”

This work was funded by a $100,000 Accelerator Grant from Lehigh. A $100,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities supports the creation of an edited volume based on Naylor's archives, edited by Edwards, Foltz and Maxine Montgomery, with publication expected in 2023, as well as the research for a second volume.

A New Approach to Literary Criticism

Inspired by her work with the Gloria Naylor Archive, research assistant Ayanna Woods ’21G completed a master’s portfolio that included two essays on Naylor’s correspondence, focusing on the exchanges between Naylor and celebrated contemporary writers Lucille Clifton and Terry McMillan.

Through this work, Woods coined a new term: intimate criticism. “[It’s] the idea that we can trace conversations about literature that function the same way as literary criticism, but only appear in informal letters between friends and colleagues. They don’t get studied because they’re not published, but they're doing the same thing,” she explains.

Naylor was a skilled writer and scholar who held visiting professorships at universities, and her expertise is apparent in her correspondence, as is the expertise of her literary contemporaries as they discuss her work and the work of others. Because of their content, these exchanges qualify as literary criticism, Woods argues.

“People have been studying and writing about correspondence between authors for a while, but it hasn't been included in conversations about literary criticism or official records of what’s been written about texts. But I think it matters, especially when it’s coming from, for example, someone like Lucille Clifton. … This is a seasoned writer and literary critic writing a really great analysis. It’s just in a letter to a friend.”

Woods is taking this idea a step further in a piece for an upcoming edited volume about Naylor.

“Who qualifies as someone writing intimate criticism?” she asks. “How do we define that? Where is that line drawn? What are the implications of drawing those lines?”

Suzanne Edwards specializes in medieval European literature and feminist/queer theory. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Mary Foltz specializes in contemporary American literature with a specific focus on ecocriticism, postmodern fiction and theory, and queer fiction and theory. She received her doctorate from the University at Buffalo in 2009.