Nationally renowned historian and author Taylor Branch discusses voting rights

The morning after his talk, Branch met with students in Tamara Meyers’ history class titled “The Global 1960s: Takin’ it to the Streets.”

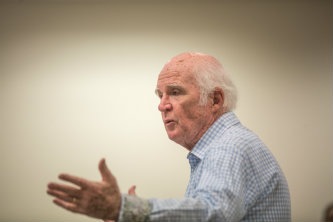

Chronicling the history of the civil rights movement was, admittedly, “not the job I was born to do,” Taylor Branch told the crowd assembled in Baker Hall on Tuesday evening for his talk, “Voting Rights: A Civil Rights Challenge Yesterday and Today.”

But growing up in the segregated South, and witnessing first-hand the devastating toll racism had – and continues to exact – on the country led to a lifetime examining and writing about the ongoing struggle through the stories of both the champions and victims of the civil rights movement.

Branch is perhaps best known for his three-volume series about the civil rights era, America in the King Years. The first book in the series, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63, won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for History and the National Book Critics Circle Award, among many other honors. He is a recipient of the 1999 National Humanities Medal, and both a Guggenheim and MacArthur Fellowship.

In introducing him, Professor James Peterson, director of Lehigh’s Africana Studies program, called Branch “one of the most visionary and accomplished historians in our nation’s history.” Professor Lloyd Steffen, who co-chairs Lehigh’s MLK Committee with Peterson, said there was little discussion about the best person to address the newly controversial issue of voting rights.

“In order to fully understand this issue,” Steffen said, “we wanted an expert who could speak to the challenges to voting rights that we face today. Taylor Branch’s chronicling of the civil rights era is considered masterful. We had no difficulty deciding who to ask.”

“Yes,” Branch said when he took to the podium, “I’ve done all those things they said about me – which means I’m pretty old.”

For the next hour, Branch led his audience through a history of the civil rights movement, much of it viewed through his perspective as a white child growing up in a segregated South. He recalled two pivotal events that bookended his formative years: the 1954 Brown vs. the Board of Education landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that ended segregated public schooling and the 1968 assassination of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King. These nationally shared developments, coupled with his personal experiences, coalesced into a lifelong yearning to deeply examine “this alien mystique about race.”

“A doctrine of equal souls”

Originally setting out to study medicine, Branch shifted his academic focus to the leaders of the movement, opting for the personal stories of those who propelled the movement. It was, for example, King’s devout faith that drove both his nonviolent approach and his moral certitude.

“For King,” Branch said, “nonviolence was at the heart of democracy for one reason: a vote is a piece of nonviolence. We are a gigantic cathedral of votes, a doctrine of equal souls. There is a religious underpinning to the concept of equal votes. King had one foot in institutional politics and one foot in the Scriptures.”

Despite the progress that King and other activists made, threats to democracy have re-emerged in restrictive voter ID laws, gerrymandering of congressional districts and localized decisions on both the number and locations of polling places. The changes are driven, he said, “by a ridiculous standard of too many people voting rather than enough people voting.”

Although burdened by “our inherited course of race relations,” Branch said that he remains “continuously awed by the courage, tenacity and political brilliance of those who cling to nonviolence.

“And what a tragedy it is that that lesson is not more widely appreciated,” he said. “Our form of citizenship is profound and we have dumbed it down – and it’s not just the hateful racists who have done that.”

Branch fielded a series of questions from the audience that touched upon a disengaged citizenry, lack of enthusiasm for protecting voting rights, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

A cataclysmic moment in history

The morning after his talk, Branch met with students in Tamara Meyers’ history class titled “The Global 1960s: Takin’ it to the Streets.” In the nearly 80-minute discussion, Branch again recounted his experience growing up in the segregated South, and witnessing a cataclysmic moment in American history.

“You have to understand,” he said, “this was a time when we were debating politics in a very different way: government was good, elections were important. There was very little cynicism about politics at a time when schoolchildren were literally having drills about hiding under your desk in a fetal position so you could survive a nuclear attack – as if that were possible. There was a basic opinion about politics and an optimism about the future. We’d licked Japan and Hitler and President Kennedy said we would conquer space. We were the good guys and we were free.”

But there was no escaping the sense that the freedom and optimism didn’t extend to all – a reality that was made abundantly clear in his daily interactions with the African Americans who toiled alongside him in the Branch family dry cleaning business.

“It was difficult to talk about,” he said. “It was a very fearful subterranean issue, and most of our lives were spent trying to find a comfortable abstract premise to justify our views on race. I guarantee you that people were very ingenious in coming up with ways to justify racism – not unlike today, when voting rights continue to be challenged.”

Branch shared aspects of U.S. history that have been ignored by many, including the role white men in the South played as part of “slave patrols,” who were given access to the homes and property where slaves were housed.

“They were ordered to ride a beat – which is the origin of police beats – to search for slaves, but also for any signs of literacy – pencils, books – because it was against the law for slaves to read,” he said.

But from underneath this yoke of oppression, he said, the powerful longing and fight for freedom and equality through civil rights movement that ultimately led to the passing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act also paved the way for advances for women, gays, and immigrants. It also led to other political, socioeconomic and cultural shifts that continue to improve the lives of countless Americans.

Yet he is not optimistic about race relations in the U.S. and places at least part of the blame on the level of our political discourse.

“I don’t think we’re going to fix it,” he said. “It would be great if people realized that it is a national issue. But even our presidential election is like high school politics, where we’re talking about who’s cool, and who’s annoying. So when something happens, someone gets shot – like a Trayvon Martin – it’s ‘Oh, we have to have a discussion about race.’

“It’s not just a discussion. It will take a long process of many people making discoveries and taking risks to fully address the issue. We’ve become too comfortable. It’s not a quick solution, and people want a quick solution so that they don’t have to talk about it.”

Photos by Christa Neu

Posted on: