Newbegin once taught an intensive English program comprised of male students from Iraq. The group met artist Khalil Allaik, LUAG’s preparator, who took them on a sculpture tour. The students, Newbegin says, “come back and tell me that not only did they feel that it really enriched and enhanced the quality of the writing they were trying to accomplish at the time, but it's something that they’ll remember in 10 years, 15 years.”

LUAG, says Newbegin, is a place for everyone: “Everybody belongs, everybody’s allowed to come and appreciate what we have here. … For every single discipline that’s offered at Lehigh, there’s a connection to the art gallery.”

Alternative Experiences: The Accessible Art Initiative

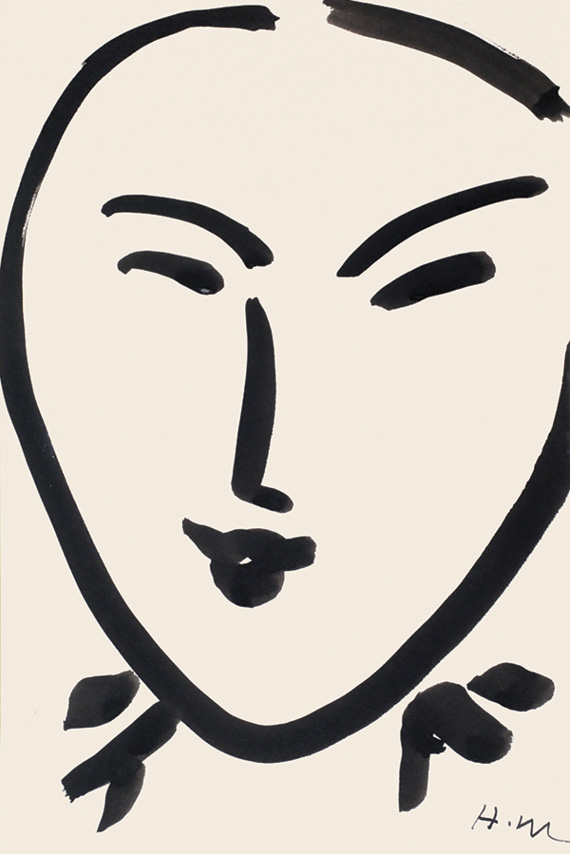

The 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) brought about a new dimension to Lehigh’s art galleries. McAndrew and the team began exploring how they might provide access to visitors with visual impairments and other disabilities through audio descriptions and tactile diagrams. The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York invited the team to participate in a tour they offer for blind visitors. They spent some time in the MOMA staff lounge and discussed different approaches to accessibility with the staff there.

“They said [Lehigh is] ahead of where some of the big museums are because we’re small,” recalls McAndrew. “They have the staff, but too much to do. We have a team of volunteer audio describers [to get it done].”

This team of volunteers—which has included McAndrew, Newbegin, Delia Chatlani, Diane DeBaune, Jane Desnouée, Linda Ganus, Vince Gentilcore, Laura Fay, Barbara Kozero, and Denise Stangl—has been trained to look at a piece of art, analyze it and describe what they see in writing. Steve Lichak of Lehigh’s Digital Media Studio records the reading of the descriptions, and LUAG makes them available via a “guide-by-cell” program. Visitors simply call a special phone number using a mobile phone to hear information about a particular piece.

A Space for Reflection, Opportunities for Growth

“We live in this visual culture,” says Wonsidler. “We’re being bombarded with images through our phones, through television, media, billboard, in every direction. But we have a remarkably visually illiterate culture in a certain way. We’re kind of swimming in it, but we don’t always know what to do with it. The museum creates a space of reflection where people can come and look at some really good examples of people thinking really hard about images and what they do and how they function in culture and feeling.”

The amazing thing about art, says Viera, is that there are many different ways of looking at it.

“You just need a point of entry,” says McAndrew. “It’s a way of connecting you with the whole history of humanity.”

Augustine Ripa, professor of theatre, has provided his voice for a number of recordings.

“I was happy to serve as a voice for the accessible art project,” says Ripa. “I'm a theatre person. When acting, we teach a process that begins with an image—a picture in one's imagination. We then let that image move us; we react to it. Only then do we express the text vocally. Acting, not reciting. It was fascinating to use this very technique with the paintings and photographs in question. Vivid images, emotional response, and only then—speech.”

Many fully sighted visitors take advantage of the audio recordings as well. McAndrew says that one visitor told her that before hearing the recordings, “I looked, but I never really saw.”

“This is helping them to see,” she says.

LUAG’s efforts are also helping visitors to feel—quite literally.

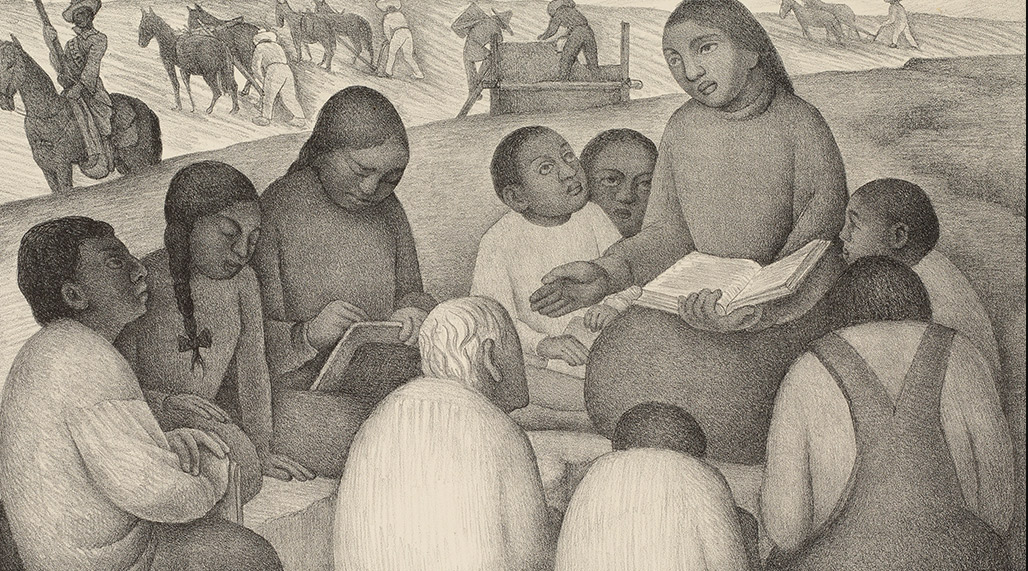

In 2015, Brian Slocum, managing director of Lehigh’s Design Labs and Wilbur Powerhouse Prototyping Lab, worked with art, architecture and design students in his 3-D Design Foundations class to create tactile 3-D representations of several artworks in LUAG’s “Of the Americas” and “Object as Subject” exhibits. Those works are now used as part of an accessible art tour.