In his mind's eye, Mark Connar '84 MBA can see it all very clearly.

He can see the imposing 19th-century stone castle-like structure on Lehigh’s Stabler Pathways property—near Center Valley Parkway in Upper Saucon Township, Pennsylvania—come to life as an interpretive museum and industrial heritage park for children, families and students.

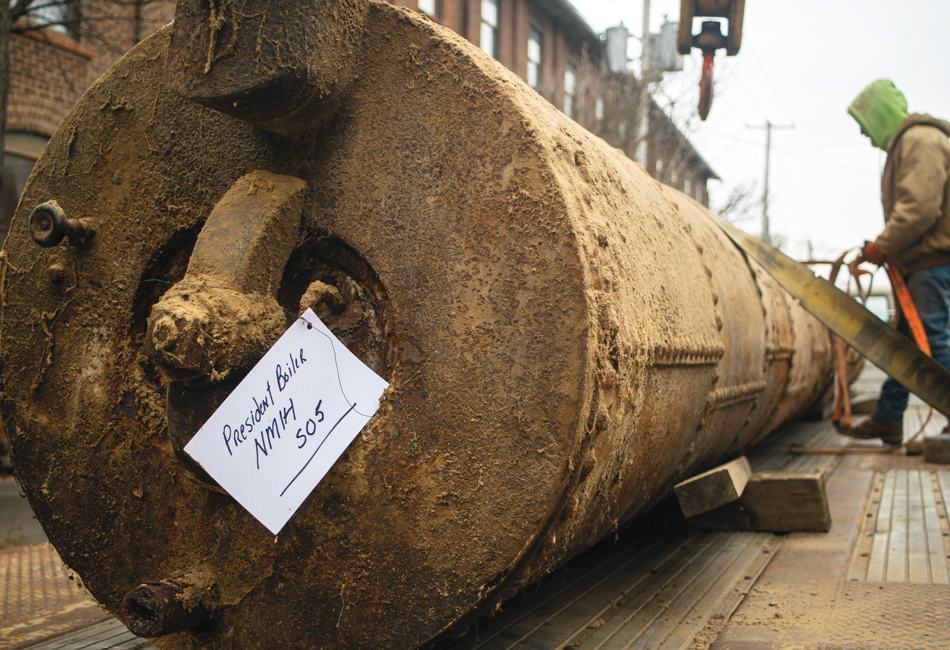

He can see the debris cleared, and the thick walls of local stone cleaned, repointed and stabilized so future generations can go inside and learn about its past as the home of The President Pumping Engine—the world’s largest and most powerful single-cylinder stationary rotative steam engine ever, which drew massive amounts of water from the zinc mine so the rich ore could be extracted.

Connar can see a circular viewing stand the size of the engine’s cylinder, over 9 feet in diameter, inside the once three-story building, an architectural achievement itself and the only pumping engine house still standing in the United States built in the style of the Cornish from Great Britain. And as he walks around the perimeter of the mining pit, now a picturesque small lake, Connar can see people strolling on a nature trail, enjoying the present as they contemplate the time when this 20-acre area was teeming with activity.