Recovering History’s Forgotten Catholic Writers

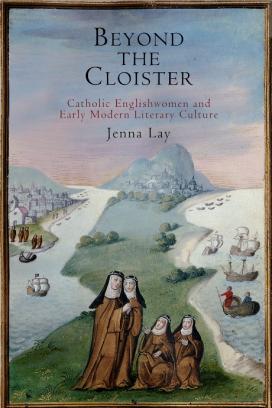

Jenna Lay examines the spiritual guides, confessions and other writings by Catholic women in the century following the English Reformation. (Illustration by Laurindo Feliciano)

Beyond the Cloister

In 1534, one year after his marriage to Anne Boleyn and his excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church, King Henry VIII became the supreme head of the new English Church through an act of Parliament.

Over the next seven years, Henry VIII closed all of the Catholic monasteries and religious houses in England—a number estimated by some historians at more than 800—and confiscated their land and wealth.

Following the dissolution of the monasteries, says Jenna Lay, an associate professor of English, some nuns remained in England and others went into exile. By the latter half of the 16th century, women who remained Catholic or converted to Catholicism often practiced their faith as recusants—individuals who refused to attend English church services. Others left for Europe to set up convents in the Netherlands, France and Spain. The exodus grew as the pace of persecution quickened under Queen Elizabeth I.

These recusants and nuns, says Lay, wrote spiritual guides, confessions, prayers, polemics and hagiographies. They wrote to raise money, they wrote to answer their critics, and they wrote to take part in the political and religious debates of the day. But their contributions to English literature have been largely forgotten.

Lay attempts to restore the literary record in her new book, Beyond the Cloister: Catholic Englishwomen and Early Modern Literary Culture. The book, her first, will be published this month by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lay spent a decade conducting research for her book, visiting monasteries and libraries in the United States and England and on the European continent, and poring over original manuscripts written in the convents.

She became interested in her subject when she discovered that nuns often appeared in works by William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, John Donne and other famous English writers in the decades following the dissolution of the monasteries.

“I wondered why these canonical writers were still interested in nuns if there were no longer any nuns in England,” she says. “A number of Shakespeare’s female characters, for example, express a desire for a life that is separate from the world. Olivia in Twelfth Night mourns the death of her brother and vows to stay at home ‘like a cloistress’ for seven years.

“I did some initial research and learned that [in the decades following the English Reformation] there were still many Catholic women in England and on the continent. I became interested in how English authors were responding to the contemporary reality of Catholic women and their literary involvement in the period.”

Lowell Gallagher, an English professor and literary theorist at UCLA, praised Lay’s diligence in searching for original source materials to support her research.

“Beyond the Cloister is an articulate and well-balanced contribution to a rapidly developing interest in early modern studies,” wrote Gallagher. “The work represents a timely and valuable reminder of the critical dividends that a genuinely materialist approach to literary history can produce.”

The measure of meaning

Beyond the Cloister has four chapters. The first, “Fractured Discourse: Recusant Women and Forms of Virginity,” discusses Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, a dark comedy that Lay teaches to her undergraduate students. (Lay introduced Measure for Measure at the Globe on Screen series at Arts Quest in August 2016.)

The play’s protagonist, Isabella, is a young woman who enters a convent but leaves when a messenger arrives to tell her to go and plead for the life of her brother, who has been sentenced to death. But Angelo, the duke’s substitute, wishes to sleep with Isabella and refuses to issue a pardon unless she submits to him.

Through a confusing series of twists and turns, many of them orchestrated by the real duke, who has been compared to a God-figure, Isabella’s brother is saved and Isabella does not accede to Angelo’s demands.

“This sequence of events,” says Lay, “points to many questions that were raised at the time by Catholics—how to relate to political authorities, to legal structures that restrict personal choice, to one’s own faith. Shakespeare plays with the texture of language to render this confusion in the formal and poetic patterns of the play. This includes the inconclusive nature of Isabella’s desire to be in the convent and maintain her vow of virginity.”

The meaning in Measure for Measure, says Lay, is found in its dialogue as much as its narrative. Its characters often speak in a recursive, or repetitive, manner, employing chiastic formulations, in which a phrase circles back on itself. The duke proposes marriage to Isabella with a chiasmus, saying, “What’s mine is yours, and what’s yours is mine.” The play’s final curtain falls, however, without a reply from Isabella, whose speeches throughout the play resist closure.

“Isabella’s refusal to reply points to the inconclusive nature of female virginity of the time,” says Lay. “It raises the question of what it means to be a vowed virgin, and to want to be a nun.”

A guest concocts a scandal

In another chapter, Lay looks at Syon Abbey, once one of England’s most prosperous monasteries. Founded by Henry V in 1415, Syon became a public center of English literary life and, says Lay, a “lightning rod for Protestant propagandists.” Following the dissolution, the monastery was demolished, and some of its nuns left for Europe, settling eventually in Lisbon, which was then part of Spain.

The nuns of Syon Abbey published manuscripts and printed books describing their travels and persecutions and dedicated some of them to King Philip of Spain. While doing research in the British Library, Lay came across a manuscript the nuns wrote in response to an exposé about their Lisbon convent, which had been written and distributed by a Protestant propagandist in 1622.

The exposé was titled “The Anatomy of an English Nunnery at Lisbon” and written by an Englishman named Thomas Robinson. Robinson, who had been a guest of the Syon nuns, claimed that priests and nuns were sleeping together at the monastery and that they had had babies and buried them in the monastery walls.

Within seven months of the publication of Robinson’s pamphlet, the Syon nuns had written what Lay calls a “point-by-point takedown” of his claims. They accused him of lying and said he had been a pirate before becoming a writer of exposés.

In the nuns’ manuscript, an allegorical character called Truth responds to Robinson’s claims in one extended section; the other sections are written in the first person plural. The document was not signed, suggesting it was a collective effort.

“The response shows a rhetorical and literary sophistication on the part of the nuns,” says Lay. “It shows that they could respond to Robinson in an exciting, flexible and sophisticated way. The nuns repeatedly get in little digs that are laugh-out-loud funny.”

Obedience first to God

In a chapter titled “A Game of Her Own: The Reformation of Obedience,” Lay takes up the case of Gertrude More, great-great-granddaughter of Sir Thomas More. In 1623, less than a century after her ancestor was beheaded by Henry VIII (for refusing to recognize the monarch as head of the English Church), Gertrude More helped found a Benedictine abbey in Cambrai, France.

“Gertrude More struggled at first with life as a contemplative nun,” says Lay. “She didn’t feel a connection to God; she didn’t feel she was able to pray properly.”

Augustine Baker, a Benedictine mystic, arrived at the convent and found that many nuns were struggling with spiritual practices. He helped them learn to pray contemplatively by reading and reflecting on the writings of other mystics, copying extracts from these writings and then writing their own reflections.

More wrote a series of contemplations on her practices and shared them with the other nuns, says Lay. Upon learning of their activities, the English Benedictine Congregation began investigating whether Baker was encouraging the nuns to disobey their confessor and their priests.

“Baker was removed from the convent, but the nuns continued their practices and resisted calls by the Congregation to stop,” says Lay.

In the 1650s, 20 years after More’s death, the convent published her Spiritual Exercises along with a lengthy letter she had written defending Baker and the nuns from the charge of disobedience. The letter, says Lay, stressed that obedience to God is more important than obedience to one’s religious superiors and echoed the conflicts over spiritual and temporal authority that had resulted in Thomas More’s death.

“Gertrude More’s language,” says Lay, “is grounded in 100 years of history but situated in a specific monastic context. She makes the case that nuns must have recourse directly to God, even if that means disobeying religious authorities. Her Spiritual Exercises defended nuns’ rights to their own spiritual practices.

“This was very important for English Catholics at this moment in history because it undermined one of the main Protestant critiques of Catholicism—that Catholics relied too much on intercessors—priests, the saints, the Virgin Mary—in their prayers to God. More and her fellow nuns suggested they could have a direct line of communication with God.”

A newer, firmer foundation

Lay’s book also includes an extensive discussion of George Puttenham (1529-90), author of The Art of English Poesy. That book’s “exclusion of Catholic women from the production and reception of poetic forms,” Lay writes, “is neither unique nor surprising: we expect nuns and recusants to be absent from the texts that helped to define early modern poetic practice.”

Although Puttenham portrays himself as a courtly figure, Lay says, the details of his life available in the legal records of his divorce paint a different picture which also underscores the ambiguities of the roles played by Catholic women in English literary history.

“Puttenham’s biography is horrifying. He was a serial adulterer and a rapist who kidnaped women and abused them. In his story there is a strange overlap, a coincidence that exposes the limits of literary history with respect to Catholic women.

“One of the women that Puttenham raped was a maidservant named Mary Champneys. Puttenham impregnated Champneys, took her to Belgium and abandoned her in Antwerp in 1565 or 1566. Her name shows up only because Puttenham’s wife mentioned it when she filed for divorce.”

Around this time, says Lay, a young woman named Mary Champney—without the final ‘s’—was living in Belgium as a waiting gentlewoman. Mary Champney entered the Syon Abbey in 1569, returned to England in the 1570s and died there in 1580.

“It is interesting to juxtapose the two experiences,” says Lay. “Mary Champneys is raped by George Puttenham, while Mary Champney becomes a nun and later resists the sexual advances of a Protestant soldier, an English captain. So we have two parallel life stories with the destinies flipped.

“Now, what if they were the same woman? What would that tell us about English literary history and stories that have not been told? George Puttenham is regarded as a foundational figure of English literary history, but if we look into the story of the Mary Champney who became a nun, we see other narratives and other foundations.”

A version of this story appears as "Beyond the Cloister" in the 2017 Lehigh Research Review.

Posted on: