The year 2025 began with terrifying scenes of one of the world’s great cities engulfed in smoke—the kinds of images that have long been depicted in works of apocalyptic fiction.

When confronted with a dystopian-like landscape such as that left in the aftermath of the Los Angeles fires, some people turn to novels and stories, seeking fictional worlds in which others face similar circumstances.

Many present-day readers are seeking comfort and prophetic wisdom in classics of the climate fiction genre. Octavia Butler’s “The Parable of the Sower” has been sent back to the bestseller list three decades after its release, while films such as “Mad Max: Fury Road” continue to draw viewers with big-screen depictions of climate-related disasters.

“We continue to be obsessed with stories of desolation, destruction and apocalypse,” said Michael Kramp, a Lehigh University professor of English whose research interests include 19th-century British literature. “They give us a way to come to terms with the legacy of industrialization with which we still live today.”

Researching late-Victorian examples of speculative fiction during a visit to the British Library, Kramp came across “The Doom of the Great City,” a mostly forgotten work from 1880 that is one of the earliest examples of urban apocalyptic fiction.

Written by William Delisle Hay, the novella tells of the destruction of London in 1882 by an insidious toxic fog, as recounted some 60 years later by one of the calamity’s few survivors.

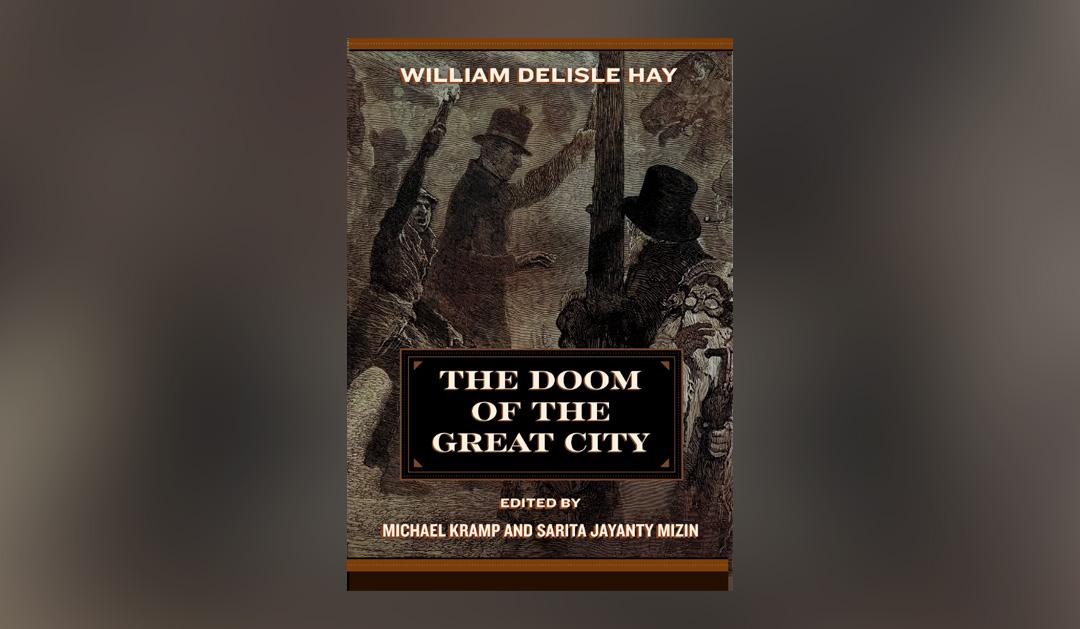

A new critical edition of the book, edited by Kramp and Sarita Jayanty Mizin ’20 Ph.D., assistant professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, was published in February as part of West Virginia University Press’s Salvaging the Anthropocene series.

In addition to the original text, the critical edition includes a scholarly introduction, bibliography and curated appendices that place the work in dialogue with key issues of the Anthropocene and the 19th century such as climate change, global perspectives on the city, the London fog, Victorian public health, Victorian suburbanization and “visions of the end.”

'The Doom of the Great City'

“The Doom of the Great City” was published in 1880, a time when Great Britain was beginning to reckon with the environmental, social and economic consequences of industrialization. New concepts in public health, including germ theory, the health impacts of pollution and the importance of sanitation, were also taking hold.

The author, who was a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, incorporates some of these then-new concepts into his descriptions of the fatal fog. But rather than fully focusing the text on the causes and consequences of environmental destruction, the author ultimately spins a moralistic tale condemning deteriorating societal structures and immoral behaviors.

Mizin notes that the narrator is capable of making incisive observations about the negative social and environmental impacts of industrialization but falls back into tired imperialist narratives and justifications.

“The narrator concludes, ‘There was money in London; for the swollen city was at once the richest and the poorest in the world: side by side with the direst degradation of poverty, there existed the superbest opulence,’” Mizin said. “However, the narrator then manipulates observations like these into implications that the impending disaster, which inevitably kills many of the most vulnerable, is somehow a deserved punishment!”

This perspective reflects the environmental, class and racial anxieties felt by Hay and other members of privileged classes of the time, Kramp argues.

“The narrator recalls how 19th-century industrialization, urbanization and pollution beget the deadly fog, but he also mourns what he presents as a lost cultural order,” Kramp writes in the critical edition introduction.

The narrator survives the fog, which is limited to the city, having traveled to visit friends in a suburban area. Traveling back into the city to investigate, he witnesses the horrors of the event. At some point thereafter, he migrates to the then-British colony of New Zealand.

In addition to presaging New Zealand’s status as a popular apocalypse-escape destination, the story reinforces colonialist perspectives and the anthropocenic shifting of climate impacts onto the Global South.

The narrator recalls the events of the book in comfort from a colonized New Zealand, one that, in his telling, has transformed from “almost a virgin wilderness” to one of the “most populous rural districts” over the 60 years since the cataclysm.

“I was taken aback by the pathetic performance of the male narrator, especially how his sentimentality and pronouncements of nostalgic remorse allow him to garner sympathy from his family and readers,” Kramp said. “In ‘The Doom of the Great City,’ Hay adopts anthropocenic logic, decimating the English capital and acting with the privilege of a Victorian imperialist.”

Lessons to Learn

Beyond its literary value, “The Doom of the Great City” offers a lens into Victorian views on urbanization, public health and empire. Kramp suggests that the novella has relevance for courses in Indigenous studies, gender studies and the health humanities, as well as literature and medicine.

The work also remains a read that will appeal to fans of Victorian literature and post-apocalyptic fiction, even if it offers little in terms of hope or productive solutions.

“Our goals were always collaborative, and what I mean by this is that we were always hoping to invite ongoing collaboration with future readers, scholars and teachers,” Kramp said. “I don’t think we offer all that many definitive statements or discover findings that determine how the novella ought to be read or studied. But I think we share possibilities that allow teachers, students and all readers to pursue different ideas and generate new kinds of knowledge.”

The new edition of “The Doom of the Great City” is available from WVU Press.

In addition, Kramp and Mizin co-edited a new critical edition of “After London; or, Wild England,” an 1885 book by Richard Jefferies that imagines how an undetermined ecological event devastates London and transforms England, its land, people and wildlife. That book is available through Clemson University Press.

Story by Dan Armstrong