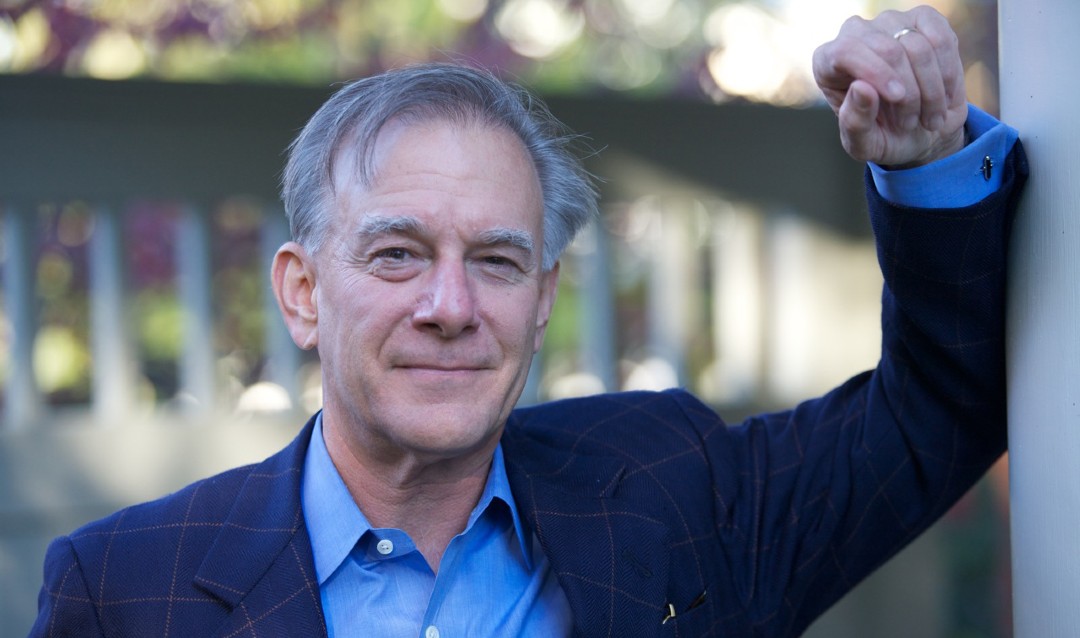

David Ignatius has had a front row seat to many major world events throughout his decades-long career as a journalist. In his delivery of the 2021 Kenner Lecture on Tuesday, he shared several pivotal experiences, which he called “snapshots,” to explain, he said, “how I’ve seen the world coming apart over my 45 years as a journalist, and how I can imagine it coming back together again.”

Ignatius addressed an audience of approximately 600 via Zoom, and he began by acknowledging the challenges of the past year.

“I want to reflect with you tonight about my own journey, not just since last March, but over the arc of my career, over the course of what I describe as this process of new world disorder. We've all lived through so many difficult things this year, every one of us: personally and emotionally, feeling isolated, worried, often politically angry and frustrated, scared about our jobs and sometimes about our country,” he said.

Ignatius reports on politics, economics and the Middle East, and has written his current twice-weekly column for The Washington Post since 1998. His more than 40-year career has seen him cover the Pentagon, Capitol Hill, Cyber Command and the CIA. He is the recipient of a number of awards, including a George Polk award for his nine-article coverage of the killing of his colleague, Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi; the Urbino International Press Award; the Overseas Press Club Award for Foreign Affairs Commentary; a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Committee for Foreign Journalists; a Legion D'Honneur from the French government; the Edward Weintal Prize; and the Gerald Loeb Award for Commentary. Ignatius has written 11 spy novels, several of which were New York Times bestsellers, and also wrote a political opera libretto, The New Prince, an adaptation of Machiavelli’s The Prince that premiered at the Dutch National Opera in 2017.

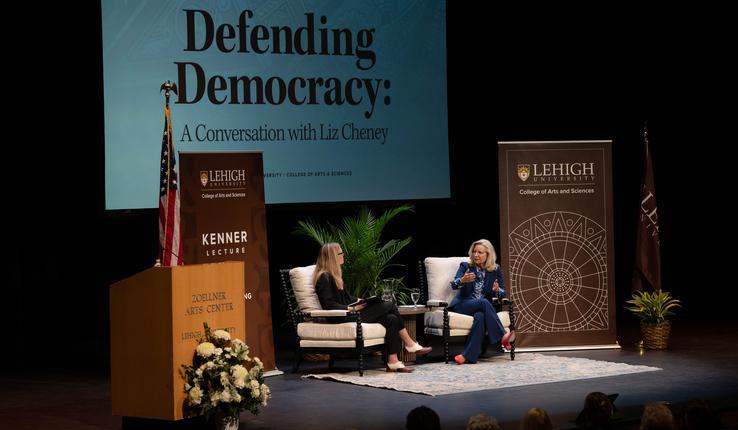

The Kenner Lecture Series in the College of Arts and Sciences was endowed by Jeffrey L. Kenner ’65 ’66. Kenner, who studied industrial engineering and business administration at Lehigh, established the lecture series in 1997. After a career as a management consultant with PricewaterhouseCoopers (then Price Waterhouse & Co.), he became involved in private equity and venture capital. Kenner formed his own firm, Kenner & Company. Inc., in 1986. He served as a Lehigh University trustee from 1995 to 2002 and provided critical seed funding for the Integrated Business and Engineering (IBE) undergraduate program. He has long been recognized as an Asa Packer Society and Tower Society donor and was inducted into Leadership Plaza in October 2000.

Snapshots of ‘A World of Disorder’

Robert Flowers, the Herbert J. and Ann L. Siegel Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, introduced Ignatius.

“The Kenner Lecture and other endowed lectures are critical to shaping Lehigh’s character. They bring to campus speakers who leave a lasting impression on our students, who then go on to make a difference in the world,” Flowers said.

Ignatius began with a snapshot of Bethlehem, Pa. His first job, covering the United Steelworkers Union and the steel industry for the Wall Street Journal in the mid-1970s, brought him to Pennsylvania’s Rust Belt, he said, and he developed “an emotional connection to Bethlehem Steel.”

“If there was a person less well-suited to covering the steelworkers than me, I'd like to know who that was,” said Ignatius, noting his privileged childhood and education. “But it changed my life. It forced me to learn how to talk to people, how to get out of that privileged upbringing, get out of my skin and get into other people's. Listen to them, listen to what they said.”

In those years, Ignatius said, he “watched the beginning of the decline of one of America’s greatest industries.” Conditions in the Rust Belt, he said, gave rise to “the anger that drove the election of Donald Trump, the anger at the global economy, the distrust of globalization, which I think has brought our country and the world great benefits but also severe costs: the uprooting of the middle class that was at the center of our national life.”

Ignatius shifted focus to Beirut, Lebanon, on April 18, 1983, where he was covering the Middle East for the Wall Street Journal. He had just left the United States embassy after interviewing a military attache when a suicide bomber destroyed the building, killing 63 people, including legendary CIA officer Robert Ames. Ignatius had written in detail about Ames, who had recruited for the CIA the chief of intelligence of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Ignatius considers that day the beginning of the United States’ war on terrorism, he said. It was also the day he became a novelist.

“I knew so much about the operations that this remarkable American CIA officer, Robert Ames, had been involved in. ... But I ended up knowing so much more in the aftermath of his death. People who’d worked with him came to me and sought me out to tell me about him. And I ended up having so much information it wasn't really possible to do justice to it, even to comprehend it in nonfiction. ... Each of [my novels] has begun with my experiences as a reporter, but that's a day that changed my life [and] that also changed our country.”

Ignatius then described a visit to Moscow in 1983, during the fall of communism. He was speaking with a Soviet dissident—a brilliant scientist who had been fired from his job and lost everything— and the man remarked on then-President Ronald Reagan’s recent speech. “[Reagan] made a speech in which he called the Soviet Union ‘the evil empire.’ And this man turned to me and said, ‘How can it be that in your country, which is so rich and prosperous, that we think might have lost its ability to see things in our part of the world, you've found a president who tells the truth about us, who calls us by our right name?’ I never looked at Reagan the same after that.”

Not every event is what it seems, and not all end well, Ignatius reflected. Such was the case in what he witnessed as an unembedded reporter during the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, he said. “At the time, so many Iraqis seemed overjoyed that we had come to overthrow Saddam Hussein. It was easy to imagine that this might be a story with a happy ending. Looking back, that really is the biggest foreign policy mistake of my lifetime, one that we're still struggling to overcome. I look back at my columns in the months before the invasion which were generally supportive, and I wish I could take back those words. It's not just the policymakers, not just George W. Bush who got that wrong. I have to include my own inability to see the dangers that were ahead,” he said.

Ignatius also recalled standing among the massive crowd that had gathered to celebrate the overthrow of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in Egypt’s Tahrir Square in 2011 during the rise of the Arab Spring. “It was a moment when you thought that anything was possible,” he said, “when people had a sense of joy. … I remember writing a column, saying that the United States was making a cosmic bet on the possibility that this transformation would work out for the best. Tragically, the Arab Spring is one of those moments where all the hopes people had really turned dark and a period of great pain and difficulty for the Arab world began.”

Back at home in the U.S., Election Night 2016 set the scene for another snapshot, in which Ignatius recalled his wife’s comment to him when Donald Trump was projected to be the winner: “She turned to me and said, ‘David, you have to do your job. Now that this man is elected president, you have to cover him and try to tell the truth about what's happened as best you can.’ And that was an injunction that I never forgot.”

In addition to covering stories such as that of former national security adviser Michael Flynn, Ignatius noted, he made a point to write about what he considered the good things the Trump administration did, particularly those related to foreign policy. He continued, though, to describe another snapshot, which he called “a real low point”: the removal of U.S. troops from Syria. “I found it heartbreaking, to be honest, when President Trump decided to essentially cut off these allies [the Syrian Kurds] and allow Turkey to invade and push them back. For me that was a painful moment for America.”

Suffering and Strength

Reflecting on the importance of journalists, Ignatius spoke of his friend and colleague, Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi journalist who was assassinated at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul by agents of the Saudi government. Ignatius said he promised himself he’d do anything he could to hold accountable those who were responsible for Khashoggi’s death.

“Every day around the world, there are journalists who risk their lives, literally, for the most basic job of a journalist, which is to report events, tell the truth, not be intimidated by governments,” he said. “Jamal Khashoggi is somebody who paid the ultimate price, but there are so many journalists who've been killed, who are in prison. Every time I meet with them I try to remember that part of our job … is to keep faith with them, to make sure that we're reporting the risks they take, the sacrifices they make.”

Despite the images conjured by some of the snapshots he shared, Ignatius said, there is still reason to hope. He spoke of his 100-year-old father, former Secretary of the Navy Paul Ignatius, who began writing essays about the things he loves to help him cope with the pandemic. Ignatius and siblings then compiled the essays into a book for his birthday.

“I'm a believer in that mental exercise of thinking through what you love, what matters, and I know that's really the secret of how he got through this difficult year,” Ignatius said.

“We've suffered a lot in this year and in recent years. Our country, certainly our democracy, had a terrible experience—I worry that it was a near-death experience—in the last few months, but we've come through it. … We've come out of this, I believe, smarter, stronger, certainly more resilient than we were at the beginning and, I think, stronger, more resilient than some people thought we might be.

“This may be a world of disorder, but the orderly parts, the parts of our country that are strong, seem to me basically as strong as ever.”