Choosing survival over victimhood

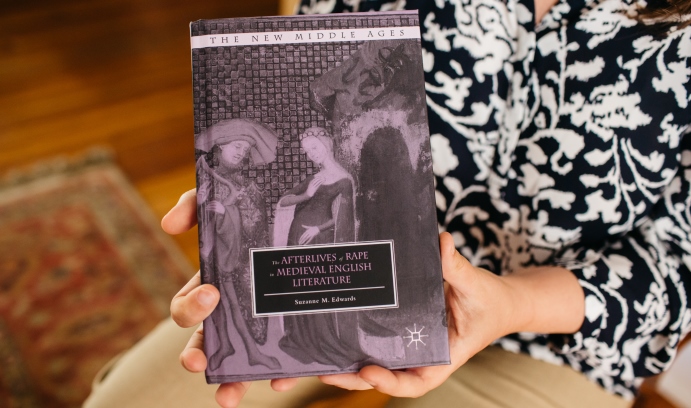

In her first book, Suzanne Edwards explores the long history, in literature and in law, of the relationship between victimization and survival.

A single word, says Suzanne Edwards, can make a world of difference.

A decade ago, says Edwards, an associate professor of English, feminists began to describe women and men who have experienced sexual assault as survivors, rather than victims.

In feminist theory and politics, she says, this focus on survival emphasizes the experiences, choices and voices of those who have endured sexual assault. Survival calls attention to women’s agency, their ability to negotiate the terms of their own lives after an assault. The language of victimhood, on the other hand, emphasizes a rapist’s actions and isolates the violent act from its effects on a woman’s life.

The relationship between victimization and survival has a long history in literature and law, which Edwards explores in her new book, The Afterlives of Rape in Medieval English Literature. The book, her first, was recently published by Palgrave MacMillan as part of a series called The New Middle Ages.

In Afterlives, Edwards analyzes a variety of texts written in England between the late 11th century and the end of the 14th century. These include the works of Geoffrey Chaucer and other writers, as well as lesser-known texts such as saints’ lives, legendary histories, legal documents and spiritual biographies.

Medieval writers and theologians did not always characterize the survival of rape in positive terms. Edwards points to the story of Lucretia as one influential example of this line of thought. This story was first recounted in Titus Livy’s ancient history of Rome, but it was retold approvingly throughout medieval Europe—often in instructional handbooks for medieval wives and in works explicitly designed to praise women’s virtue.

Lucretia, wife of a Roman nobleman, committed suicide after her abduction and rape by the son of a tyrannical king. Her kin’s outrage at the prince’s crime fueled the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 B.C.

“In the Middle Ages,” says Edwards, “there are many examples of women being encouraged to kill themselves rather than survive rape, just as Lucretia had in the lead-up to the founding of the Roman Republic. For example, St. Jerome counseled suicide as a form of rape prevention, citing Lucretia and Catholic saints like Pelagia who killed themselves to avoid suffering sexual violence.”

At the same time, Edwards says, another strain in medieval thought celebrates survival. “I looked particularly for cases where writers see survival as a good thing. I read these texts as resources that may have helped women choose to survive.”

For instance, Augustine of Hippo, the Catholic theologian and saint, argued against suicide in the aftermath of rape. In City of God, he sought to console Roman women raped during the fall of Rome in the fifth century and he urged them to see their lives, rather than their deaths, as testimony to their suffering and their courage.

In her book, Edwards traces the legacy of medieval English discourses on the aftermath of rape. She argues that these discourses are relevant to contemporary controversies about sexual violence, on college campuses and in international human rights law.

Ravishment or elopement?

Edwards, who is also the director of Lehigh’s Humanities Center, spent 11 years conducting research and writing her book. She traveled to the United Kingdom’s National Archives to study medieval legal records and consulted texts written in Middle English, Latin and French.

Afterlives has four chapters: “Rape Survivors and Living Martyrs in the Lives of Holy Women,” “Looking at ‘Strange Women’: Pedagogies of Sexual Violence in Anchoritic Literature,” “Outrage Against Rape and the Battle over Survival in Fourteenth-Century Legal Discourse and [Chaucer’s] Wife of Bath’s Tale,” and “Ravished Wives, Sovereignty and Political Reform.” An afterword is titled “Afterlives in the 21st Century.”

In one chapter, Edwards examines a notorious 14th-century legal case, which led to a change in the law regarding sexual violence that was encoded in the 1382 Statute of Rapes. In the case, she says, a nobleman and his wife, Thomas and Alice West, write about what they characterize as their daughter Eleanor’s ravishment (abduction and rape), but was more likely her elopement with a young man whom the parents deemed unsuitable.

“In this case,” she says, “the parents’ outrage over rape became the rhetorical and moral rationale for circumscribing their daughter’s choice of a husband. The parents’ argument was that Eleanor’s rape meant that her subsequent choices could not be viewed as autonomous. This family dispute was ultimately framed as a conflict over survival: Could a woman’s own will survive her rape? Eleanor’s parents thought not.”

The English parliament agreed with the parents, Edwards says. “The law was changed to treat a rape victim as someone who was legally dead, who could neither inherit property nor exercise marriage choice.”

Imitatio Christi

In addition to legal debates, Christian teaching and theology heavily shaped medieval thinking on the aftermath of rape, says Edwards.

“There is a long history in the Middle Ages of understanding the psychic and physical pain associated with rape and survival in terms of Christ’s redemptive suffering and resurrection. In Latin, the term for this suffering is imitatio Christi. The suffering of the faithful becomes a way to participate with Christ’s sacrifice and become more like him.”

The idea that imagined suffering might have redemptive value, called affective piety, meant that men and women did not necessarily have to suffer physical wounds to identify with Christ.

“I found that, in texts addressed to religious women, identification with Christ’s suffering sometimes took the form of seeing oneself as a survivor of sexual violence—whether or not that woman had in fact endured rape.”

The idea that being a survivor had spiritual worth shows up in two texts that Edwards explores: the Life of Christina of Markyate, a 12th-century anchoress (religious recluse) who spurned marriage, and the Book of Encouragement and Consolation by Goscelin of St. Bertin, which was addressed to a nun named Eve of Wilton. Both works, she says, imagine that rape can be endured for the sake of faith. Both present the survivor of rape as a “holy virgin martyr who achieves redemptive sacrifice by living in shame rather than dying in glory.”

The historical record, says Edwards, contains few first-hand accounts by survivors of sexual violence. The texts she studied were written almost exclusively by men, who had more access than women to the time, training and other resources that a writer needs. Even legal records, she says, represent the summaries of male clerks, which mediate the stories women told about their own experiences. A modern student must read between the lines.

“The fact that men wrote the texts does not mean that they tell us nothing about women,” she says. “After all, women were often the subjects and the audiences for the texts. For example, although texts for anchoresses were definitely written by men, they were clearly addressed to women and perhaps sometimes commissioned and shaped by women.”

Society’s responsibility to survivors

Another reason for the dearth of survivor accounts may be difficult to grasp in the modern age of instant and constant communication. In the Middle Ages, says Edwards, silence itself was a form of communicating.

“In the Middle Ages, the idea of telling a story to understand survival in the aftermath of rape was foreign. But silence could be a powerful form of agency when associated with survival after rape. Today we often associate silence with the deliberate suppression of women’s voices. But medieval texts frame a survivor’s silence as itself courageous, particularly when a victim of rape refuses the finality of suicide and returns to a community.”

A survivor’s return, she says, raises the question: What is the community’s responsibility to her? Augustine in City of God, Chaucer in Wife of Bath’s Tale, and the anonymous writer of Sir Orfeo, a medieval poem that retells the Greek myth of Orpheus, all wrestled with this question.

“All three texts propose different answers to that question,” says Edwards. “For Augustine, the question is how to console women who have suffered the unreasonable shame of rape. He believed the community had a responsibility to see the survivor as a profound mirror of the human condition itself, the extent to which all kinds of circumstances put a person’s will at odds with their bodily experiences.

“The Wife of Bath’s Tale, which is perhaps the most famous rape narrative written in the Middle Ages, explores the tension between a community’s responsibility to punish rapists, and thereby do justice to the injuries a victim has suffered, and the problem of understanding a survivor only in terms of her violation rather than in terms of her ongoing life and relationships.”

For Edwards, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath’s Tale suggests that legal justice is not, by itself, ethically sufficient for communities’ obligations to survivors.

Finally, by urging communities to see survival as a political act, Sir Orfeo offers a stark contrast to the Legend of Lucretia. The latter features a tyrant king, a rape, a suicide and a revolution. It presents Lucretia’s suicide as the incentive for political change. In Sir Orfeo, a king’s wife is abducted and suffers sexual violence at the hands of a fairy king, but survives and returns to a welcoming community.

“Sir Orfeo, which rewrites a Greek myth that ends with the woman’s death, shows how medieval writers were imagining forms of political change that could encompass survival rather than demanding women’s suicide as testimony to their rapes and evidence of tyranny.

“It’s a small, but meaningful, change to represent a community’s acceptance of a ravished noblewoman.”

A mattress as a relic

How relevant to the modern world are the written records of bygone ages? In her book, Edwards discusses feminist reforms in international criminal and human rights laws that have defined rape, by itself, as a crime of genocide. She points out that this legal change is important in recognizing how gender shapes experiences of war, but she also wonders how equating rape with death in international law affects how women see survival.

“To treat rape as a form of murder or as worse than death, as some feminist legal reforms do,” she says, “might foreclose conversations that we still need to have about survival and what survivors need beyond legal punishment of their rapists.”

Finally, Edwards argues that medieval representations of rape and survival shape cultural responses to a recent case of on-campus sexual violence.

Emma Sulkowicz, a former Columbia University student, protested the school’s handling of her rape allegations against a classmate. Her accused rapist was found “not responsible” in a university investigation.

In response, Sulkowicz carried a 50-pound mattress around campus during the 2014-15 academic year and to Columbia’s 2015 commencement ceremony as well. This endeavor, submitted as her senior thesis, was titled Mattress Performance: Carry that Weight and received national media coverage.

“Emma Sulkowicz staged an incredible performance piece, carrying the mattress on which she had been raped,” says Edwards. “We think of her actions as a very contemporary political concern, but many cultural responses to Sulkowicz’s protest draw on the Passion narrative, as with medieval texts that associate survival with Christ’s sacrifice.

“For instance, I found references to Sulkowicz’s performance in light of the Stations of the Cross, the steps in Christ’s journey to his crucifixion, and to her mattress as a relic, the items associated with saints that Catholics preserve and venerate.

“How someone comes to see herself as a survivor of sexual violence remains a pressing question, as much today as in the Middle Ages. Similarly, we continue to wrestle with how communities are ethically obligated to survivors, beyond issues of crime and punishment.

“For me, exploring these questions means shifting our critical attention from the act of rape to the condition of survival. It also means abandoning the presumption that conversations about sexual violence and survival today have nothing in common with those that were taking place in the Middle Ages.”

Story by Kurt Pfitzer

Photos by Christa Neu

Posted on: