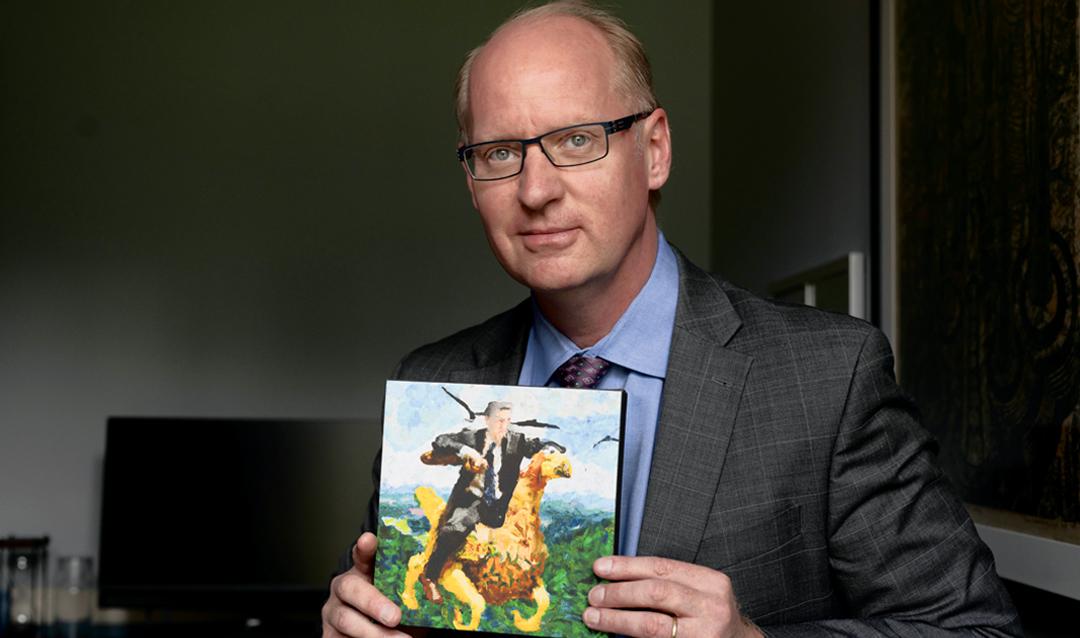

In his office in Lehigh’s Alumni Memorial Building, Provost Nathan Urban displays this canvas: a man sporting a gray crew cut, dark business suit and dangling blue tie sitting atop a mythical creature that’s a cross between a dragon and a hawk. The two soar over green treetops, the distant mountains visible in the background.

The bold brush strokes that look like thick paint are reminiscent of Van Gogh, but no painter created this image.

The canvas was made by DALL-E 2, a deep learning model developed by OpenAI, an American artificial intelligence company, to generate digital images from descriptions called “prompts.”

It was a gift from Chris Kauzmann, interim director of Lehigh Ventures Lab, who asked the generative artificial intelligence (AI) platform to create an image of “a university provost riding a mountain hawk in the style of Vincent Van Gogh.”

The picture serves as a visual aid for Urban, demonstrating the capabilities of generative AI—and its drawbacks. DALL-E created a fictional mountain hawk that Urban says he would have never imagined, but its depiction of a provost is “not surprisingly, a white man in a suit and tie” rather than someone of another gender or race.