‘An overlay of meaning’ in life

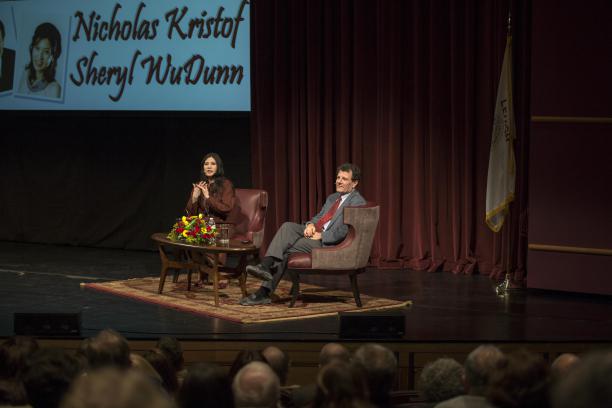

Sheryl WuDunn and Nicholas Kristof, who in 1990 became the first married couple to win the Pulitzer Prize, delivered the 2015 Kenner Lecture on Cultural Understanding and Tolerance to a packed audience in Baker Hall.

Sheryl WuDunn began with a question.

“What would you do if there were a drug that could make you happier, make you possibly live longer, [make you] be a better person, with no major side effects? Would you take it?”

The drug, it turns out, is the act of engaging with the world.

WuDunn and her husband, New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof, delivered the 2015 Kenner Lecture on Cultural Understanding and Tolerance to a packed audience in Baker Hall Tuesday evening.

WuDunn and Kristof won a Pulitzer Prize in for journalism in 1990 for their coverage of China’s Tiananmen Square democracy movement. They were the first married couple to win the award. Kristof, whose op-ed columns appear twice a week in The New York Times, won a second Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of genocide in Darfur. WuDunn is currently a senior managing director with Mid-Market Securities, where she raises capital for a variety of clients. Together, Kristof and WuDunn have written several bestselling books, including Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide and A Path Appears: Transforming Lives, Creating Opportunity.

Donald Hall, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, introduced Kristof and WuDunn.

“The Kenner Lecture routinely brings to campus speakers that often jostle our commonly held views and challenge us to see things from a new perspective … Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn continue that tradition,” Hall said. “A hallmark of the Lehigh education is our students’ ability to anticipate and lead change to view challenges as opportunities, to turn knowledge into action and to make a difference in the world. These moments help our students grow, reflect, find meaning and hopefully develop a sense of direction. We also hope it sparks a productive dialogue that will continue long after tonight’s event.”

WuDunn began by sharing statistics about the problem of inequality in the United States.

“In 2010, 93 percent of the additional income created in America went to the top 1 percent ... The median household wealth in the U.S. among white households is 18 times greater than that of black households. That’s actually greater than the disparity in South Africa during the time of apartheid,” WuDunn said.

According to a recent poll, however, 97 percent of Americans agree that every American should have the right to opportunity, she said. “That shifts the problem from the idea of greater inequality to the idea of greater opportunity … Often the political debate gets centered on the rich and the poor and everyone having the right to become rich. Getting rich really means having the opportunity to get rich. That’s why everyone can agree on [focusing on] opportunity.”

WuDunn shared the story of Khadijah White, a young homeless girl who, keenly aware of her own potential, took advantage of any opportunities she could find and eventually graduated from Harvard University. “She knew she had lifelines,” WuDunn said, in the individuals who provided opportunities along the way. Even if a child is born “behind the starting line … that doesn’t mean you can’t save someone.”

Empathy, Kristof said, is key. “You do what you can to try to build empathy, to try to expose kids to a sense of their good fortune, winning the lottery of birth.”

“I do think that in a larger sense for all of us, our lives are busy, they’re hectic, there’s so much going on … that if we can find some outlet, some mechanism, some way of connecting to a purpose larger than ourselves, then it does provide an overlay of meaning in our lives,” Kristof said.

Kristof addressed what he calls the “empathy gap” in America.

“We have this robust research [about intervention efforts] now in a way we did not a generation ago,” Kristof said. “The challenge becomes why don’t we do more with it? There, I think, one of the challenges is not so much a knowledge of what will make a difference but, if you will, it’s something of an empathy gap.”

Kristof said that one of the most cost-effective ways of breaking the cycle of poverty in America is to prevent teenage pregancy, as many other countries work to do.

“Partly because of this empathy gap, we have this narrative about how poverty is all about personal irresponsibility. And there’s no doubt that there is personal irresponsibility that is sometimes a factor… But when we as a society have ways of intervening and don’t in ways that just about every other country does, then that is a social responsibility on all of our parts that we haven’t exercised,” Kristof said.

Kristof told the story of Olly Neal, a young troublemaker in a segregated Arkansas high school in the 1950s. When Mrs. Grady, the librarian whom Neal had frequently reduced to tears, noticed Neal stealing a book from the library, her impulse was to confront him. Instead, she realized he was embarrassed about checking out a book. Unbeknownst to Neal, Grady made multiple 70-mile trips to Memphis to purchase additional books by the same author for Neal to find on the library shelf, which he promptly stole as well. Neal eventually became a voracious reader, graduated from high school and went on to become one of Arkansas’ first African American judges.

“When one is willing to take a risk on people, at times the results can be remarkable,” Kristof said. “There are all kinds of times when you can try to make a difference and it doesn’t work. Everybody who has tried to help here and there has had their heart broken sometimes. But every now and then you can take a risk on somebody—maybe somebody who doesn’t even fully deserve it—and yet it can have this transformative impact that affects them and ripples through their life and the lives of so many other people.”

Kristof and WuDunn encouraged students to see the world, leave their comfort zones, learn about the lives of others both locally and abroad and find ways to help.

“The fact that we are at Lehigh right now, that we are in this auditorium, truly means that in some sense we have won the lottery of life. And when you win the lottery of life there are some obligations that go with that,” Kristof said. “I think that in exercising them one can find enormous satisfaction and purpose. It can be that drug that Sheryl talked about at the beginning. That’s it. That’s engaging with the world.”

The Kenner Lecture is an endowed lecture series of the College of Arts & Sciences established in 1997 by Jeffrey L. Kenner '65. Kenner is the founder and president of Kenner & Company, Inc., which specializes in leveraged buyouts and recapitalization of closely-held companies. Kenner also provided funding for the Kenner Theatre in the Ulrich Student Center, a classroom in the Rauch Business Center, the entrance road to campus and initial program endowment for the Integrated Business and Engineering undergraduate program.

Story by Kelly Hochbein

Photos by Christa Neu

Posted on: