Duncan MacRae Payne ’63, an international relations major, loved traveling and history– passions he merged by collecting maps, particularly those dating to the 16th through 18th centuries.

When Payne died in August 2021, he bequeathed some of his most important atlases to Lehigh University Libraries Special Collections. Those atlases will be on public display for the first time as part of an exhibit of maps in Linderman Library. “Where Do We Go From Here? Maps and Atlases from the Duncan Payne and Lehigh Libraries Collections” will open Aug. 21 and continue through the Fall 2023 semester.

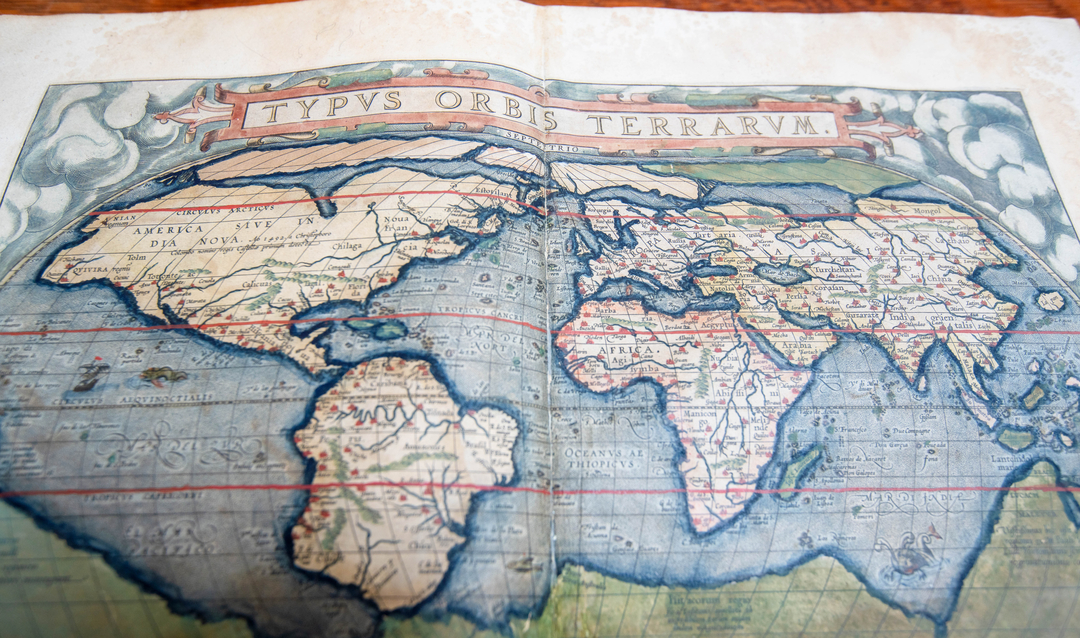

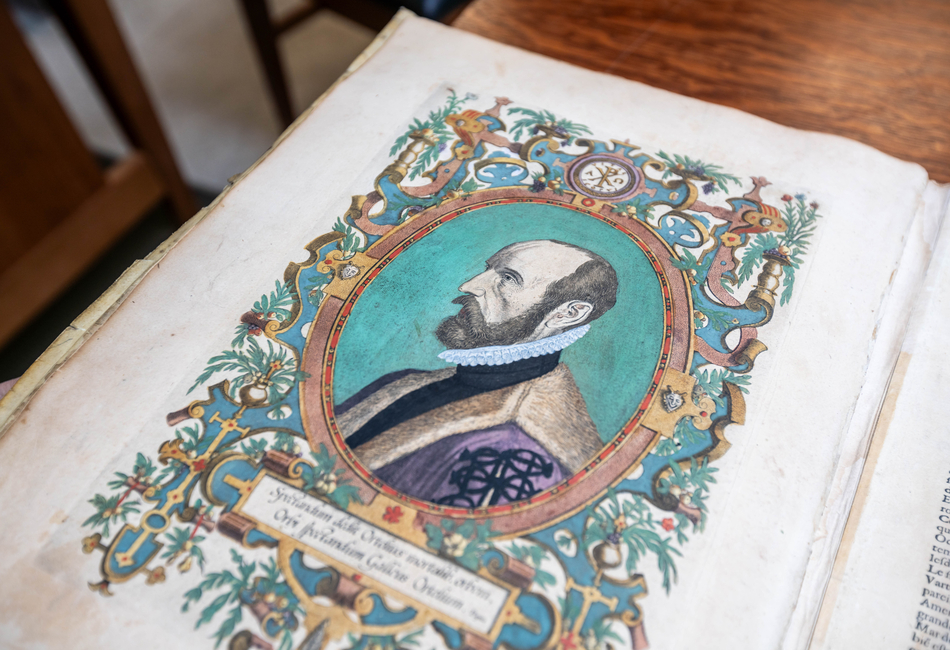

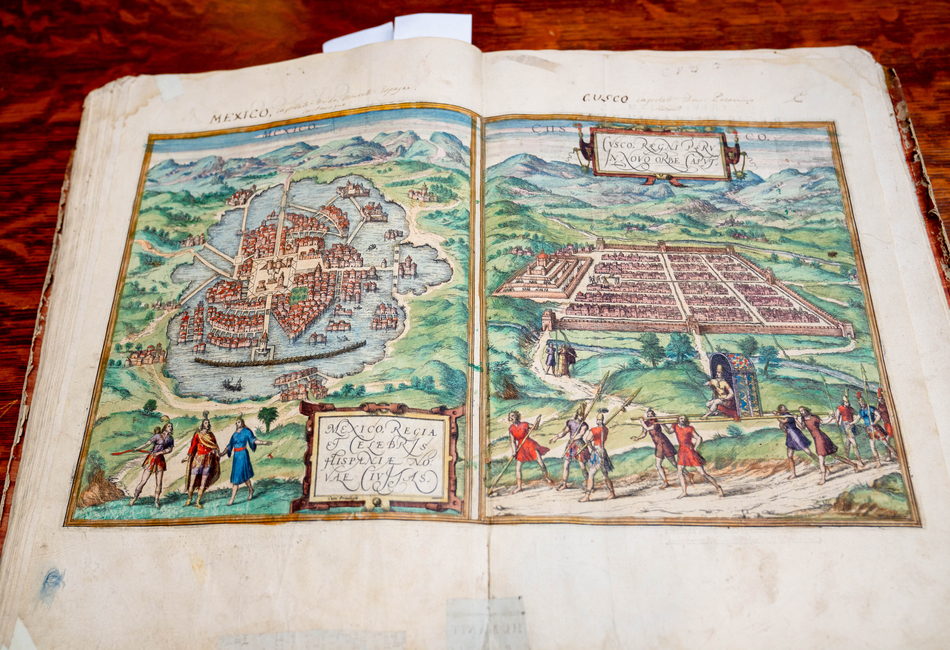

The intricate hand-colored maps, some dating back to 1575, depict the geography of the world at the time, as well as reveal the politics, social norms and even the mythology people believed in.

“Maps were so important and near and dear to him, and so was Lehigh,” said Payne’s daughter Eliane Dotson, co-owner of Old World Auctions in Richmond, Virginia. “He wanted Lehigh to be able to start an amazing collection as well as for the students there to have access to this type of historical artifact.”

In addition to the maps, Payne also made other gifts to Lehigh, including those to support financial aid and scholarships.