The entire team contributed to the DEBUT proposal (the challenge solicits design projects that represent “innovative solutions to unmet health and clinical problems”). And they spent more than two weeks on what was, for many of them, their first work as coauthors. Their proposal was one of 76 such applications. In total, 400 students from 47 universities in 26 states applied for the DEBUT Challenge.

“This is a nationwide design competition between biomedical engineering programs,” says the project’s lead mentor Xuanhong Cheng, a professor of bioengineering and materials science and engineering in the Rossin College. “So this is great recognition for these students. I’m very proud of them.”

Four student groups have contributed to the project since its inception in 2018. Their work led to two previous awards: a VentureWell grant in 2019, and a Davis Projects for Peace award in 2020.

“Each group definitely pushes the project forward,” says Cheng.

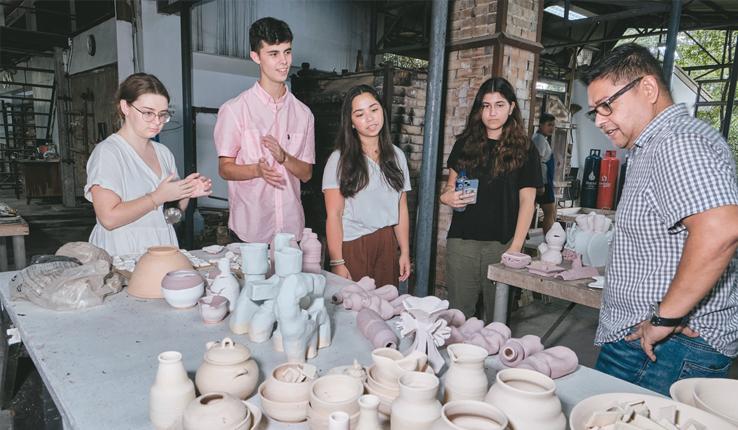

The Sickle Cell Anemia Diagnostic Device project is part of the Global Social Impact Fellowship (GSIF) program led by Khanjan Mehta, vice provost for Creative Inquiry and director of the Mountaintop Initiative. GSIF attracts students from across the university who are interested in addressing sustainable development challenges in low-income countries like the Philippines, Kazakhstan, and Sierra Leone. Students learn to work across disciplines and cultures, conduct original research, conduct fieldwork (in normal times), and perhaps most importantly, contribute to making a real impact on tough problems.

Sickle cell disease is one of those problems. The genetic condition causes red blood cells to become sickle-shaped, which impedes blood flow, and causes infection, fatigue, and severe pain. Sierra Leone has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the world, and Cheng says that many of the country’s healthcare providers believe undiagnosed sickle cell disease may be partly to blame.

“The doctors were estimating that up to 90 percent of kids with sickle cell disease don’t survive past age five,” says Cheng, who first visited Sierra Leone in 2018 with Mehta and a team of Lehigh faculty to assess project opportunities for the GSIF program. “There’s no cure, and there’s no effective treatment other than managing the symptoms.”

It’s hard to manage a condition that never gets properly diagnosed at birth. But labs in Sierra Leone lack access to simple, reliable tests that can quickly detect the presence of sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait. (Infants with the latter are asymptomatic, but they carry a single mutated gene that increases the risk that their own offspring could have the disease.) Cheng returned from her trip in 2018 convinced that Lehigh students could help develop a test that could compete with—and improve upon—those that were currently serving resource-limited areas.

“It’s been proven that early screening can help decrease the mortality rates of those with sickle cell disease,” says Pang. “And so our goal is to develop an affordable, sensitive, point-of-care lateral flow device that shows results in less than 15 minutes.”

The device will work like a pregnancy test, detecting the proteins that reveal sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait. It’s currently in the alpha testing phase, meaning the team is working to increase its sensitivity, decrease its cost, and understand how it compares with similar devices on the market.

The potential for the device is huge from a health perspective. But the project itself has already had a significant impact on the perspectives and plans of team members like Duffany.

“I think the most exciting thing about research is realizing the global implications of it,” she says. “This experience has really inspired my curiosity, and I’m considering a different career path as a physician scientist. If that doesn’t work out, I’ll probably come back to research, because I have this foundation now, and a real passion to solve these problems.”

For Pang, who has been working on the project for more than two years, the research experience has not only influenced her trajectory (she wants to go to grad school and focus on medical devices) but also taught her valuable lessons. For one, it’s okay to fail.

“In research, there’s going to be a lot of failure,” she says. “I’ve learned how to deal with that, what to take away from it, and how to move on.”

She’s also learned that she’s not the follower she always thought she was. She came into the project with little knowledge of sickle cell disease or how to do the lab work, and for the longest time, she looked to the seniors in the group for guidance. But now she’s the one answering the questions and sharing what she knows.

“I’ve become a leader for our team, and I never imagined myself in this position,” she says. “It’s definitely given me a lot of confidence to realize that I have the capability not only to problem solve but also to pass on the knowledge that will help the team carry on this project for years to come.”

Story by Christine Fennessy