Whistleblower Tyler Shultz delivered a riveting account of the unraveling of the blood-testing startup Theranos to a Lehigh audience Tuesday―an ongoing saga that pitted him against his grandfather, former Secretary of State George Shultz, and that led to the dissolution of the company and the filing of criminal charges against its founder, Elizabeth Holmes.

Shultz’s retelling of the story, which was punctuated with humor, laid bare the ethical and personal challenges he faced in recognizing problems with the company’s technology, research and quality-control practices.

Shultz quit Theranos following his repeated efforts to get the company’s founder to address his concerns, then faced about $500,000 in legal fees in the aftermath. With his relationship with his grandfather―a Theranos board member― strained, Shultz alerted state regulators to the company’s questionable practices and became a confidential source for Wall Street Journal reporter John Carryrou, who detailed problems at Theranos in published articles.

“I’ve grown a lot as a person. I’ve learned a ton,” said Shultz. “But sometimes I still think that what I’ve learned is not worth the price that I paid. And if I could go back in time and give myself advice, I would say, ‘Don’t do it, just quietly resign and move on with your life.’ But knowing me, I know that I would ignore my own advice and I would still do it.”

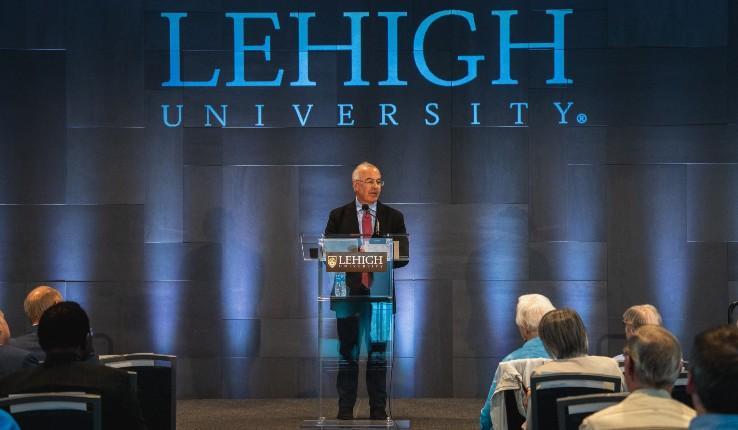

In a conversation-style format guided by graduate student Gill Andrews ’18G , Shultz delivered the third Peter S. Hagerman ’61 Lecture in Ethics to a packed Room 101 in Packard Lab. The event was sponsored by Lehigh’s Center for Ethics. Andrews, a doctoral student in English, is a member of the center’s student advisory committee.

Shultz said he first met Holmes in his grandfather’s living room and, impressed with her vision of being able to test for a number of medical conditions from a small sample of blood, sought work at Theranos as an intern. He joined the company full-time after graduating from Stanford University in 2013. As part of the company’s assay validation team, Shultz said he became aware that Theranos’ blood-testing devices were not working as touted, that blood test results were inaccurate and that state regulators were being misled.