The predominant narrative about the rise of modern art can make it seem as though the movement was limited to major metropolitan areas, like Paris, New York and Berlin. It wasn’t, says Nicholas Sawicki. “Until very recently, the way we looked at the map of the art world of the early 20th century has been quite constrained, and hasn’t taken into account the many other centers where modernism emerged, which are really interesting in their own right,” he says. “Right now, we’re seeing a major reappraisal of that history, particularly within museums and public institutions, as well as in individual scholarship.”

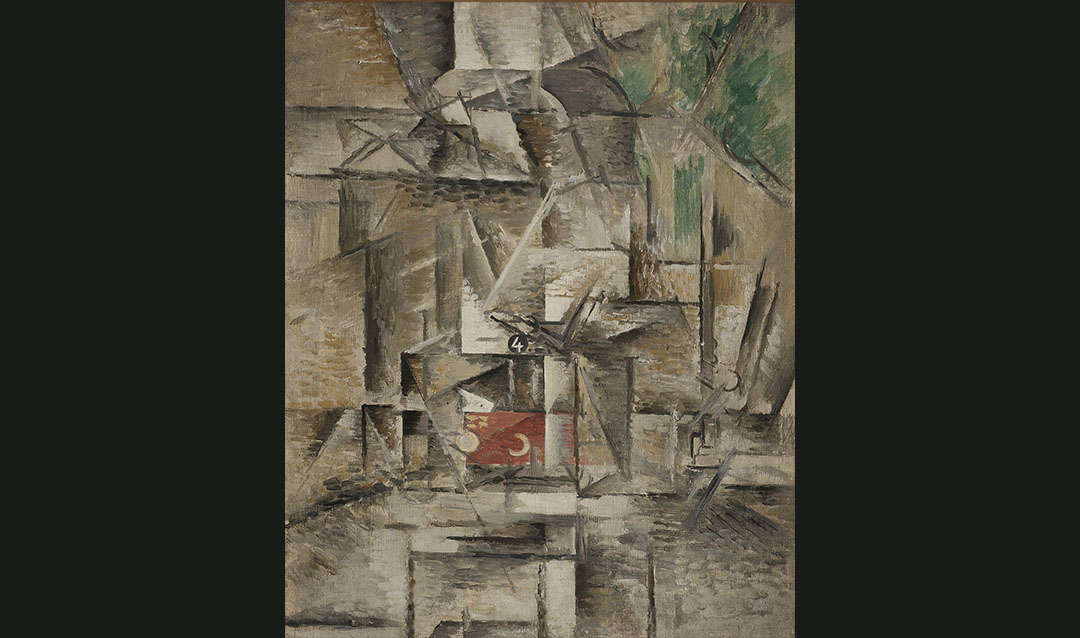

Sawicki, an associate professor of art history in the department of art, architecture and design, studies how modern art in the early 20th century developed in parts of Europe not traditionally seen as dominant artistic centers, with a particular focus on central and eastern Europe. Specifically, he examines how Cubism, one of history’s most radical and influential artistic developments, evolved in Prague, how historians and curators across the world have told the story of Cubism’s broader development, where that story might need diversification or expansion, and how to make it more accessible to more people.

“Cubism is today still seen as a gateway movement for modernism, and rightly so,” Sawicki explains. “It had an enormous impact on the art world. But it’s also true that it developed in a far more open and unbounded way than we commonly accept. So there’s a lot at stake, I think, in further fleshing out and diversifying its history.”

The Storytellers of a Movement

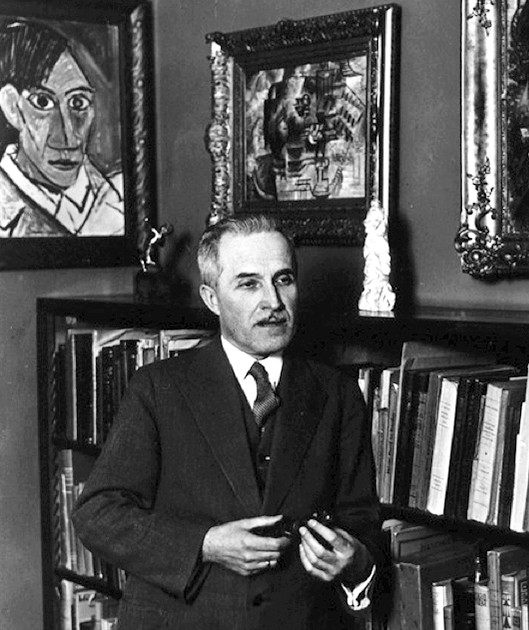

In spring 2019, Sawicki served as Distinguished Scholar at the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There, he collaborated with museum colleagues on the digitization of modernist primary sources, and advanced his own research on two early collectors of Cubism who also narrated the movement’s history: the British-born collector Douglas Cooper, and Vincenc Kramář in Prague, who owned one of the largest collections of Pablo Picasso’s work before World War I.