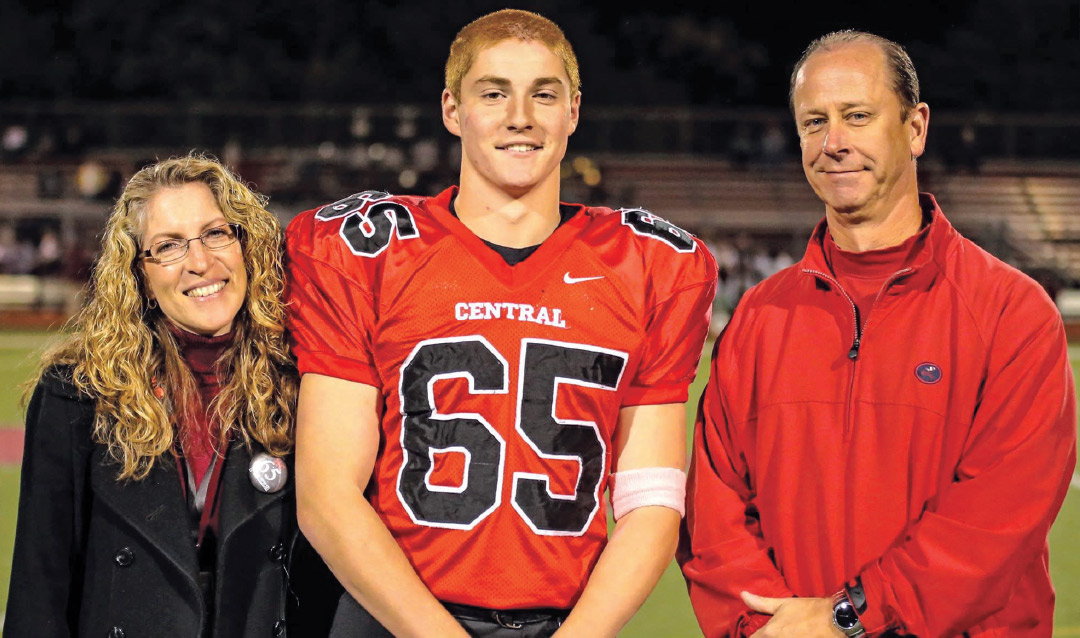

Evelyn and Jim Piazza’s 19-year-old son Tim was pledging at a fraternity at Penn State University in 2017 when, as part of a hazing ritual, he was made to binge-drink an excessive amount of vodka, beer and wine. Intoxicated, he fell several times, including down a set of stairs. No one called for medical help for 12 hours, and by then, it was too late to save him.

The Piazzas, who have since launched a nationwide anti-hazing campaign, met with Lehigh students Jan. 31 to discuss both the dangers of hazing and the need to seek medical help for those in distress. They were joined by Rich Braham, whose 18-year-old son Marquise committed suicide in 2014, following hazing at Penn State, Altoona.

The Piazzas recently sat down with the Bulletin’s Mary Ellen Alu to talk about their son, the new state law that bears his name and their mission to end hazing and save lives.

Tell me about your son.

Evelyn: He was a big guy. He was like 6-2, 6-3, kind of shy, awkward, but really funny, really genuine and nice, the most loyal friend, such a good boyfriend, like, he wanted to make sure that his girlfriend knew she deserved good things and that she deserved to be treated well.

He wanted to develop prosthetics. He really had his heart set on that. We’re not sure how he got interested in that work. He must have seen something on the internet with a 3-D printer, like a prosthetic limb. And he took engineering classes in high school and loved the 3-D printer. So I’m guessing he thought that was so cool, that you can do that and help somebody, and he really liked helping people.

When you talk with students, you vividly describe the day Tim died, from the perspective of Tim’s older brother, what he saw at the hospital. Why is that important for students to hear?

Evelyn: Because when they’re hazing, they’re not thinking about how badly things can go. I want them to know how devastating it is to see your younger brother covered in bandages with machines everywhere breathing for him and monitoring temperature and IVs, and what the doctors are saying, because they’ve already told your parents that his brain injury is nonrecoverable and he’s brain dead. I want them to feel what that feels like. And to watch from the hallway when they perform CPR on him, and then he dies. And for what? Why?

I want to drive that point home, why did this have to happen? This was so easily preventable. If [the fraternity brothers] had just called for help when they knew he was hurt ... but they didn’t want to get in trouble.

Jim: You want to put them into that place, so that if they get themselves into a situation where they’re doing something like that, hopefully their mind goes back to that place that she put them in when she was doing her presentation, and they say,

“Got to call for help for that person because we’re not doctors.” That’s what we try to instill upon them, get the person help.

When you talk to college students, do you focus on hazing or the importance of getting help?

Evelyn and Jim: All of it.

Jim: You know people are going to make mistakes, and there are going to be situations that have nothing to do with hazing where somebody needs help. We want them to call for those, too. But people are going to make mistakes, and haze, and we want other people who see that to say, “No, you can’t do it here, not on my watch.” And if something goes wrong, we want them to say,

“All right, this is out of hand. We’ve got to call for help.”

Evelyn: I want them to see what happens if you don’t call for help. This could be on your conscience for the rest of your life, to know that you could have done something but now somebody’s dead, and so many people are devastated, just devastated.

What do you want the takeaway to be?

Evelyn: Hazing is against the law. Don’t haze. It’s not necessary.

It shouldn’t be a part of your college experience, or anybody’s

college experience. You wouldn’t do it to your younger brother or sister, so don’t do it to anybody else. ...

Jim: One of the things we’ve learned from talking to President [Eric] Barron at Penn State and a lot of the leaders at the national fraternities that we’ve now interacted with is that the alumni are a big part of the problem. At Beta Theta Pi at Penn State, as we understand it, the alumni are the ones who had brought back these hazing-type activities, the ritualistic-type activities. It had been banned from Beta Theta Pi. They were a no-alcohol, no-hazing fraternity.

Under the new Timothy J. Piazza Anti-Hazing Law, colleges and universities, as of January, had to put reports of hazing violations online. Did you look at the reports? Any surprises?

Evelyn: We looked at Penn State.

Jim: I know a lot more goes on than was reported. And then some of the things that people had to do, I was surprised at. But then you have parents who are like, “Oh, this isn’t really bad. It’s not really hazing. It’s good for them.”

Evelyn: [They say,] “cleaning the house, that’s not really hazing.” Well, yeah, it’s a gateway, and it escalates. Before you know it, they’re driving in the middle of the night and being sleep deprived. And they’re being locked in the basement and told to drink a handle themselves and fill a trash can full of vomit, and being paddled.

Jim: We’ve learned that it does progress. There are a lot of

situations that no one ever hears about—we’ve heard about them now—because people don’t die, they survive. They go to the hospital. They’re near death in many cases, but they survive.

Why is the public reporting of incidents important?

Evelyn: It’s a valuable tool for parents, if they can easily see hazing violations. When Tim said he wanted to join a fraternity and which one, I looked it up online, and it was a glowing website, saying it’s a non-hazing, non-drinking fraternity, and I thought, “Oh, he made a good choice. I’m OK with this.” But we didn’t know that the fraternity had been suspended, however, many years prior, for a couple years. ... It was just a glowing, rosy

picture.

How do you begin to change the culture if so much of it is accepting of hazing and fed by peer pressure or a fear of not belonging?

Jim: Awareness. I bet among the families [who have lost children to hazing], we’ve touched over 50,000 students who have touched other students. It’s that extrapolation—and we’re only getting started—that we hope creates an awareness, not only among students, but parents, so that parents are having discussions with their children that we didn’t have a chance to have.

Is this a calling?

Jim: This is what we have to do. We’re working on a model state [hazing] law right now that’s almost ready to go, and we have, probably, a half-dozen states that we’re ready to take it to, to try to get them to change and strengthen their laws. At some point, if we can get it at a federal level, that would be awesome, but we understand that that would be difficult.

Evelyn: But [the law] needs to be a deterrent.

What can colleges and universities do differently?

Jim: When it’s new student orientation and Greek life orientation, they need to have somebody speaking about this. When they have programs for parents, they need to have a Greek life session which really deals with the truth—not just Greek life, other organizations too. And when they see or hear something’s happening, they need to investigate and take proper

action.

Evelyn: It’s got to become [as concerning as] drunken driving. We need hazing to be so negatively perceived that it’s the rarity, it’s the anomaly, that everybody thinks, “Oh no, we can’t haze.”

Your message appears to be resonating.

Jim: Yes, because it’s tragic, it’s awful.

Evelyn: If it could happen to Tim, it could happen to anybody. It wasn’t like he needed to belong. He wasn’t always falling prey to peer pressure. He didn’t go to parties in high school, because you weren’t supposed to drink. He would rather hang with his friends and play basketball, or workout, or go out with his girlfriend or play video games. He was just a normal, everyday, good kid who I guess thought that these people liked him and wanted him, and he trusted them, and he paid the ultimate price.