As a horror film, Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out certainly broke new ground. Yet, the film is firmly rooted in what Dawn Keetley refers to as “...the longstanding tradition of the political horror film” which is “...driven by very human monsters.”

The Monster is Us: Jordan Peele’s 'Get Out' Exposes Society’s Horrors

New essay collection edited by Dawn Keetley explores how the film ‘Get Out’ revolutionizes the horror tradition while unmasking the politics of race in the early 21st century United States.

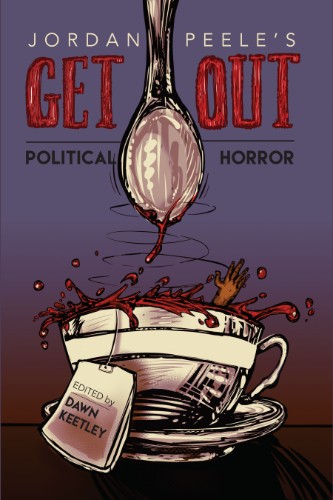

Keetley, a scholar who specializes in Film, Television, and gothic and horror among other areas, edited a recently published collection of 16 essays about the critically-acclaimed film. The book, “Jordan Peele’s Get Out: Political Horror,” is the first scholarly publication to examine the film, which grossed $255 million worldwide, was nominated for four Academy Awards and won the award for Best Original Screenplay.

In the film, Chris Washington, a young Black man living in Brooklyn, gets lured into a fatal scheme by his White girlfriend, Rose Armitage, and her monied, liberal family while visiting them in upstate New York: “The off-putting family visit immerses Chris in a world of microaggressions that get progressively more unnerving, even sinister, culminating in the terrifying moment when he realizes he has been seduced into a deadly trap. Knocked unconscious, Chris wakes up in the family’s basement strapped to a chair and watching a video that tells him he will be undergoing an operation, the Coagula procedure, that will transplant a white man’s brain into his head,” writes Keetley.

Keetley places Get Out in the political horror tradition while noting its contribution to the genre: “Since I’m an avid horror film fan, it was particularly important to me to take up Get Out within the horror tradition―something Peele himself certainly did and has spoken about,” says Keetley. “As much as Get Out emerged from horror films of the past, it also grew from the politics of the present, and so the second major aim of this collection was to read Get Out within the racial politics of its historical moment, although this moment was also, of course, rooted in the racial politics of the past—in slavery, Reconstruction and Jim Crow.”

She writes that in interviews about Get Out, Peele “...has self-consciously chosen to designate it a ‘social thriller’―a film, as Peele describes it, in which the ‘monster’ is society itself.” She notes how he has explicitly cited the influence of three films in particular: Night of the Living Dead, Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives. Peele draws on these films to: “...unequivocally indict white people in the same way that The Stepford Wives controversially indicted men,” writes Keetley.

In her introduction, Keetley also explores such topics as how Get Out utilizes the tradition of body horror to address the ongoing legacy of U.S. slavery; how blackface imagery is used in the film to “...expose the false allyship of progressive whites”; and, how the horror trope of the brain transplant is used to illustrate the persistence of racism. Keetley writes: “Racial identity and racism, Get Out proposes, are not easily dislodged―remaining mired in flesh and blood, entrenched in the very substance of the brain.”

The Politics of Horror

The collection is grouped into two sections―Part I: The Politics of Horror and Part II: The Horror of Politics. The topics in the first section range from the appearance of zombies in Get Out to how it fits into horror’s “minority vocabulary” to the movie’s place in the Female Gothic tradition.

“What most surprised me about the essays in this collection as they came in was how diverse the readings of Get Out were,” says Keetley. “Contributors took up similar scenes and read them in different ways, in different contexts. Editing these essays gave me a vastly renewed appreciation of Peele’s genius in creating this film—a film that has so many layers, so many resonant details. Each scene, each object in a shot, has meaning, often multiple meanings.”

In “A Peaceful Place Denied,” Robin R. Means Coleman, professor and vice president and associate provost for diversity at Texas A&M and Novotny Lawrence, associate professor at Iowa State University, trace the history of “Whitopia” in the horror genre, a term they attribute to Rich Benjamin and define as communities that “remain willfully less multicultural.”

“Within the horror genre, films advanced storylines of White preservation through segregation as Whites and even White monsters fled to Whitopias (e.g. A Nightmare on Elm Street, 1984), thereby freeing themselves from the dangers of the urban,” write Means Coleman and Lawrence. “All this racialized spatial angst finds its origins in D. W. Griffith’s 1915 horror film (yes, it is a horror film) The Birth of a Nation. Nation has fueled White racism for over a century by depicting northern Blacks (portrayed by Whites in blackface) as trampling upon and destroying Whites’ Southern homeland and cultural traditions.”

Means Coleman and Lawrence detail a “cinematic intervention” in the 1970s “that cut against stereotyped notions of Black communities as monstrous” with the advent of Black Exploitation (Blaxploitation) films centering Black heroes and experiences. They also recount the dominant narrative of the 1980s when, as explained by scholar Adilifu Nama, “...the urban became Reagan-era political shorthand for all manner of social ills that people of color were held accountable for, such as crime, illegal drugs, poverty and fractured families.”

The opening scene of Get Out, they write, sets the stage for an inversion of the notion of White suburbia as an oasis in contrast to threatening Black urban environments. “Get Out begins with Andre Haworth, outside his Black urban home of Brooklyn, talking to a friend on his mobile phone while walking through an unspecified neighborhood, or perhaps more appropriately, any Whitopia, USA.”

When Andre is grabbed, drugged and thrown into the trunk of a car by a masked man, the reversal is clear, they write: “The scene is disturbing as it brings the threat posed to Black urbanites to fruition, instantly constructing the well-manicured, sterile Whitopia as monstrous.”

The Horror of Politics

Topics in “The Horror of Politics” section include the construction of Black male identity in the White imagination and how historical slave resistance informs the film. An essay by a recent Lehigh graduate student Cayla McNally called “Scientific Racism and the Politics of Looking” traces the dark history of racism in science and medicine, arguing that the latter’s “dispassionate prejudice” has been “a mainstay of white supremacy since the founding of the United States.” Chris, though, is able to level his own gaze, through his camera lens, at the scientific system that wants to co-opt his body in the name of science.

In his essay “Staying Woke in Sunken Places, Or the Wages of Double Consciousness,” Mikal J. Gaines, assistant professor of English at Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, finds an “ideological affinity” between certain themes in Get Out and W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of “double consciousness.”

Gaines writes: “Du Bois sought to articulate how being black in America brings about an internal cracking open of the self, a split that ironically renders it impossible to separate questions of subjectivity (one’s internal sense of being in relation to the rest of the world) from those of identity (externally imposed and systematically enforced categories of difference.)”

As part of the Coagula trap, Rose’s mother Missy Armitage hypnotizes Chris, imprisoning his consciousness in a psychic no-man’s land dubbed “the sunken place.” “The visualization of ‘the sunken place’ in particular shares an intellectual and conceptual kinship with Du Bois’s hypothesis,” writes Gaines. The sunken place “literalizes the paralysis that accompanies being forced to occupy a splintered sense of self as a principle condition of life.”

While Get Out, as Keetley notes, “emerged from the politics of the present,” the film transcends it to wrestle with larger questions. As Peele himself has said: “The best and scariest monsters in the world are human beings and what we are capable of especially when we get together.”