‘Styrofoam’ Planet May Help Solve Mystery of Giant Planets

An artist’s rendering of KELT-11b, a “Styrofoam-density” planet recently discovered by Lehigh astronomers that orbits a bright star in the Southern Hemisphere. (Image by Walter Robinson/Lehigh University)

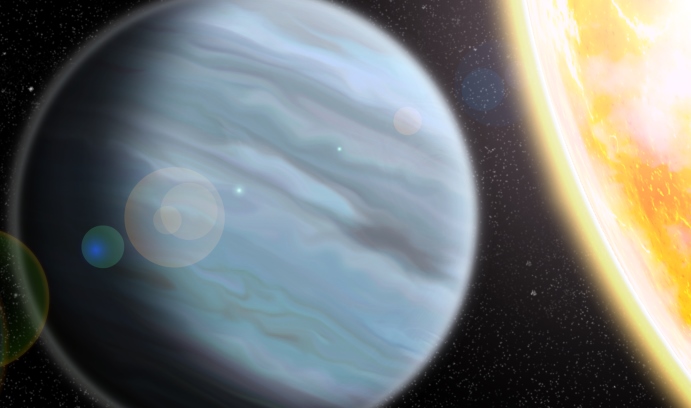

Fifth-graders making Styrofoam models of the solar system may have the right idea. Lehigh researchers have discovered a new planet orbiting a star 320 light years from Earth that has the density of Styrofoam. This “puffy planet” outside our solar system may help solve the long-standing mystery of the existence of a population of highly inflated giant planets.

“It is highly inflated, so that while it’s only a fifth as massive as Jupiter, it is nearly 40 percent larger, making it about as dense as Styrofoam, with an extraordinarily thick atmosphere,” said Joshua Pepper, astronomer and assistant professor of physics at Lehigh, who led the study with researchers from Vanderbilt University and Ohio State University, along with researchers at universities and observatories and amateur astronomers around the world.

The research, “KELT-11b: A Highly Inflated Sub-Saturn Exoplanet Transiting the V+8 Subgiant HD 93396,” is published in The Astronomical Journal.

The planet, called KELT-11b, is an extreme version of a gas planet, like Jupiter or Saturn, but is orbiting very close to its host star in an orbit that lasts less than five days. The star, KELT-11, has started using up its nuclear fuel and is evolving into a red giant, so the planet will be engulfed by its star and will not survive the next hundred million years.

While inflated giant planets have been known for more than 15 years, their existence still eludes a clear explanation. The extreme nature of the KELT-11b system makes it unique and may help researchers to solve this puzzle, Pepper said. The planet’s host star is extremely bright, allowing precise measurement of the planet’s atmospheric properties and making it “an excellent system for measuring the atmospheres of other planets,” Pepper said. Such observations help astronomers develop tools to see the types of gases in atmospheres, which will be necessary in the next 10 years when they apply similar techniques to exoplanets with next-generation telescopes now under construction.

The KELT (Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope) survey uses two small robotic telescopes, one in Arizona and the other in South Africa. The telescopes scan the sky night after night, measuring the brightness of about five million stars. Researchers search for stars that seem to dim slightly at regular intervals, which can indicate a planet is orbiting that star and eclipsing it. Researchers then use other telescopes to measure the gravitational “wobble” of the star—the slight tug a planet exerts on the star as it orbits—to verify that the dimming, called a “transit,” is due to a planet and to measure the planet’s mass.

Scientists and citizens search the sky

Pepper built the two telescopes used in the KELT survey, which he runs with researchers at Vanderbilt University, Ohio State University, Fisk University and the South African Astronomical Observatory. Among the more than 30 contributors to the research are partners at NASA, Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton University, and the University of California at Berkeley. Lehigh physics graduate student Jonathan Labadie-Bartz is a member of the KELT team and a co-author on the paper. Some 40 “citizen scientists” in 10 countries across four continents have also contributed to the KELT project. Several contributed directly to the discovery of KELT-11b and are co-authors on the paper.

While several projects using small robotic telescopes have found hundreds of planets orbiting other stars—and space telescopes like the NASA Kepler mission have discovered thousands—most of those planets orbit faint stars, making it difficult to measure the planets’ properties precisely.

“The KELT project is specifically designed to discover a few scientifically valuable planets orbiting very bright stars, and KELT-11b is a prime example of that,” Pepper said. The star, KELT-11, is the brightest in the southern hemisphere known to host a transiting planet by more than a magnitude and the sixth brightest transit host discovered to date. Planets discovered by the KELT survey will be observed in detail by large space telescopes such as Hubble and Spitzer and the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2018, to understand how planets form and evolve and how their atmospheres behave, Pepper said.

The KELT researchers set out to discover gas giant planets orbiting bright stars, but did not expect to find planets with such low mass and large sizes. Located in the southern sky, the “extraordinarily inflated” KELT-11b is the third-lowest density planet with a precisely measured mass and radius that has been discovered. “We were very surprised by the amazingly low density of this planet,” Pepper said. “It’s extremely big for its mass. It’s got a fifth of the mass of Jupiter but is puffed up into this really underdense planet.”

Though researchers are debating the cause of KELT-11b’s inflation, “the fact that the host star is in a short-lived phase of its evolution, racing toward the final stages of its life, might provide a clue,” said Scott Gaudi, a co-author, one of KELT’s principal investigators, and Thomas Jefferson Chair of Astronomy at Ohio State University. As the star runs out of fuel, it has started to inflate and is encroaching on the orbit of KELT-11b, bombarding its planet with ever more radiation.

“This additional radiation may cause close-in planets like KELT-11b to inflate like a balloon,” Gaudi said of the planet’s exceptionally low density. “Additional study of KELT-11b and systems like it are needed to explore this possibility.”

Research at Ohio State University was supported by a National Science Foundation CAREER grant. Other contributing authors were supported by grants from NSF and NASA, along with funding from participating universities and foundations.

Story by Amy White

Posted on: