Study Reveals Untapped Creativity in U.S. Workforce

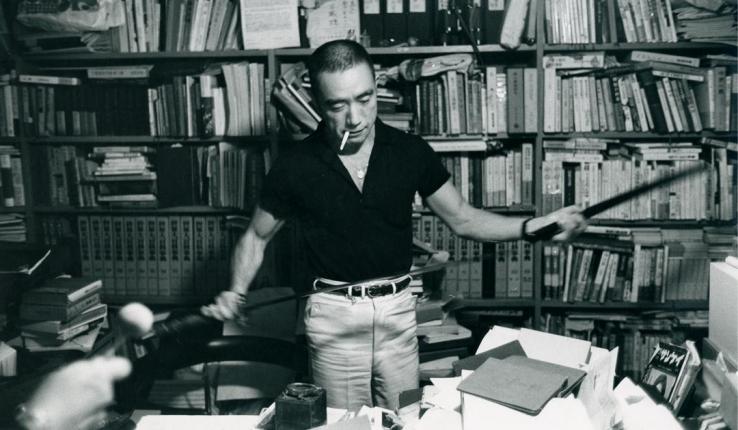

The study by Lehigh sociologist Danielle Lindemann and others was titled “‘I Don’t Take My Tuba to Work at Microsoft’: Arts Graduates and the Portability of Creative Identity.” (Image courtesy of istock/SetsukoN)

As the U.S. economy relies less on manufacturing, creativity and innovation are increasing in value. Arts graduates, and others who have developed and honed their creative skills, can be critical assets.

There are millions of arts and design graduates in the U.S. workforce. Research shows that the majority of arts alumni—more than 90 percent—have worked at some point in their lives at jobs not related to the arts.

However, according to the authors of a new study that looks at how people with arts degrees view their creativity as translatable to their current jobs, many arts alumni are not channeling their creative skills and abilities across the economy.

The study will be published in the November edition of American Behavioral Scientist in an article titled “‘I Don’t Take My Tuba to Work at Microsoft’: Arts Graduates and the Portability of Creative Identity.” The authors are Danielle J. Lindemann, assistant professor of sociology and anthropology at Lehigh, Steven J. Tepper of Arizona State University and Heather Laine Talley of the Tzedek Social Justice Fellowship.

In the article, the researchers use data from the 2010 survey by the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP), along with a study of double majors conducted with the support of the Teagle Foundation, to explore the translatability of arts alumni’s creative skills to their current jobs.

The authors found that many arts alumni—in both arts-related and non-arts jobs—are not leveraging their creativity across their lives. They explain that though workplace context factors—such as working environments that do not encourage creativity—play a role, individuals with creative training may be limiting themselves because their own senses of creativity are too narrow. These individuals believe their artistic training and creative skills are relevant in some contexts but not others.

“We were able to get information about thousands of people with arts degrees, and the jobs they have now, and find out how they think about the relationship between their arts training and their occupational trajectories,” says Lindemann. “The SNAAP sample size was large enough that we could look at people who received the same training and ended up in the same occupations and compare their orientations toward their current jobs. That’s never been done before on this scale.”

“Side-by-side narratives”

According to Lindemann, the researchers were interested in the concept of “creative identity”—how people who think of themselves as creative, and who are trained to be creative, do or do not view that creativity as “portable” into various occupational contexts.

“Do arts graduates who now work as attorneys, teachers, computer programmers, etc., feel that their creative training is relevant to their work?” she asks.

For the SNAAP portion of the project, the researchers were mainly interested in asking respondents to explain, in their own words, “how your arts training is or is not relevant to your current work.” They found that people with similar training who are working in similar jobs interpret the relationship between their creativity and their work differently.

For example, one former music major, in describing the applicability of his arts training, wrote:

“Relevant in working with others and needing to consider people skills like in the band. Not relevant because I don’t take my tuba to work at Microsoft.”

Another individual explained:

“I use the technical skills on my instruments as a tool and backdrop for most of the creative work I do, with or without the instrument.”

The authors write that their preliminary evidence suggests “…that one factor in these divergent responses may be respondents’ creative identity—the extent to which these individuals viewed themselves as creative, and, specifically, their sense of how their own creativity extended across contexts. For some, creativity was portable into their current jobs while, for others, it was not. Some took their tubas to the office, in a figurative sense, while others left them at home.”

Lindemann adds, “I think for me the most striking thing was the side-by-side narratives of people who worked in the exact same job and who had such different thoughts about whether their creative training was applicable to their jobs.”

An example of one “side by side comparison” can be found in the responses of two arts-graduates-turned-attorneys. One said his creative training translated to the legal sphere: “The communication skills and creative thinking I learned at [arts school] really help with lawyering.”

The other attorney did not view his arts training as relevant to his work. In fact, he described the “creative” domain of the arts as being in opposition to the “thinking” zone of the law. “I’m a lawyer,” he said. “Arts is creative. Law is thinking.”

“One person who works as an attorney,” says Lindemann, “will say that his creative training is invaluable to his ability to do his work, while another will say it’s irrelevant, because the law involves ‘thinking,’ not ‘creativity.’ Why is that?

“Some of those differences may be due to workplace context or their specific positions in their firms, but, as we explore in the article, we think their identities as ‘creative people’ play a crucial role as well.”

Does more artistic training translate into greater creative satisfaction?

In their analysis, the researchers look at arts graduates who spend the majority of their working lives in an occupation outside the arts. They found that 51.8 percent of undergraduate arts alumni report being “somewhat” or “very” satisfied with their opportunity to be creative in their work. By comparison, 60.3 percent of graduate alumni say they are “somewhat” or “very” satisfied with their opportunity to be creative in their work.

The authors find a positive relationship between increased artistic training and satisfaction with opportunity to be creative in what might be seen as “noncreative” jobs.

They write, “If we think about educational level as a rough proxy for commitment to creative identity, these results bolster the findings we have indicated above: arts alumni with more ‘salient’ creative identities are more likely to experience their creativity as durable in ‘noncreative’ contexts.”

In addition to being of interest to those with a stake in workforce development, the study results may be particularly relevant to arts educators. According to the authors, while most arts curricula focus on preparing students for specialized arts careers, the vast majority of arts graduates end up working in other contexts.

The authors write, “The way that students are socialized in arts school has consequences. Romanticizing the work of artists to too great an extent may produce students who take too narrow a view of what it means to think creatively and to engage in artistic work. Arts educators may wish to draw on our results in setting the stage for how their students think about their creative capacities in the workplace, both in arts fields and beyond.”

Story by Lori Friedman

Posted on: