Professor wins architecture award for Christmas City huts

Nik Nikolov won the American Institute of Architects Award of Excellence for his Weihnacht huts, a functional and luminous feature of Bethlehem’s Christmas City Village.

The challenging task of the huts’ design—simple and elegant, festive and functional—fascinated Nik Nikolov, assistant professor of architecture, when Bethlehem’s Downtown Business Association approached him with the project in 2013.

The pro bono project had, as Nikolov describes, “two specific, very quirky” requirements: First, the 35 huts had to be easily stored, constructed, taken apart and stored again by volunteers each year before and after the Weihnachtsmarkt. Second, as the city had little money for the project, they had to be inexpensive to build.“It was a perfect sort of storm of problems and parameters,” says Nikolov, who is also a practicing registered architect in Pennsylvania. “It had to be cheap, it had to be simple, it had to come and go away easily, it had to not require specialized labor for installation and had to withstand the wind and the weather in December. ... That perked me up completely because it’s a really interesting problem.”

An elegant solution

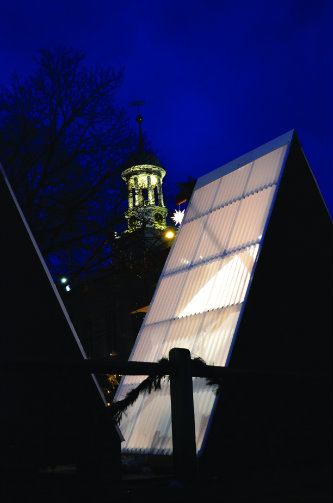

Nikolov’s solution to that problem was just as interesting—so much so that the Eastern Pennsylvania chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) recently recognized him with the AIA Award of Excellence, given by an independent jury of architects “for the best built project of 2015 that exhibits excellence in architectural design and promotes urban and environmental sensitivity.”The huts, which feature translucent polycarbonate roofs that allow them to glow festively from within, appear uncomplicated. They are, however, fairly complex, says Nikolov.

“One of the big conversations I always have is that good minimalist architecture is incredibly complex because anyone can draw a triangle,” he explains. “[But] there’s a lot more that happens between the drawing and the actual durable structure because you have to deal with not only how you build it, but how it’s going to survive and last the elements.”

Some of that complexity, in this case, stemmed from the strict parameters of the project. Issues of construction, labor, storage and money prompted Nikolov to distill what could be a far more complicated system into something more minimal. He paid close attention to how things came together and how the structure’s main elements—the roof, for example—might perform the functions that additions like gutters might.The steeply sloped huts, borrowed from a Moravian vernacular type of architecture, allow snow and rain to slide off, rather than collect. The polycarbonate panels used for each roof allow heat from the sun to collect in the hut like a greenhouse during daylight hours, keeping the interior warm and comfortable for vendors and customers alike. The huts’ economically and environmentally friendly design generates no waste. The polycarbonate panels and 2-by-4-foot rafters are standard lengths, requiring no cutting. The backs and fronts consist of 4-by-8-foot panels of plywood, from which every triangle cut is used in another structure. The materials for each hut cost approximately $280, an amount that is a particular source of pride for Nikolov.

“[We were able to be] ultimately efficient with the material,” he says.The deck, walls and roof panels are also easily assembled, requiring only nails and wood screws for construction. Nikolov and his young children were able to assist volunteers with the building the first year. The single units can later be flat-packed, transported in a flat-bed truck and easily stored for the following year.

'The mouse that roared'

Nikolov feels a sense of satisfaction in seeing his design become a signifier of a local tradition, a seasonal, luminous installation visible at night from Route 378. Recognition from the AIA for his work adds another level of gratification. He calls the project “the mouse that roared.”

“This is strictly a professional award, and as such it’s a great recognition for your colleagues to recognize that you did something worthy of being ‘best of,’” says Nikolov. “It is also a special source of pride for me because it’s seen in the context of all these legacy [architectural] offices that do multimillion-dollar projects.”

With the Award of Excellence, says Nikolov, AIA recognizes that the simplicity of the Weihnacht huts functions on several levels.“It’s transformative on a cityscape in some modest way. But still it does more than, I would argue, what a lot of historical buildings do. It also functions on a kind of theoretical, at least conceptual, level that ties into discussions about prefabrication and economies of scale, but also signifiers, historical precedence and heritage, the kind of shape that is seen. And it ultimately asks the question, ‘Why do we build the way we do?’”

This particular project, with its elegant simplicity, proves Nikolov’s point: You can do a lot with little.

Posted on: