Nuclear Fusion: Wrestling with Burning Questions on the Control of 'Burning Plasmas'

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER). Photo by EJF Riche July 2018 Credit: © ITER Organization, http://www.iter.org/

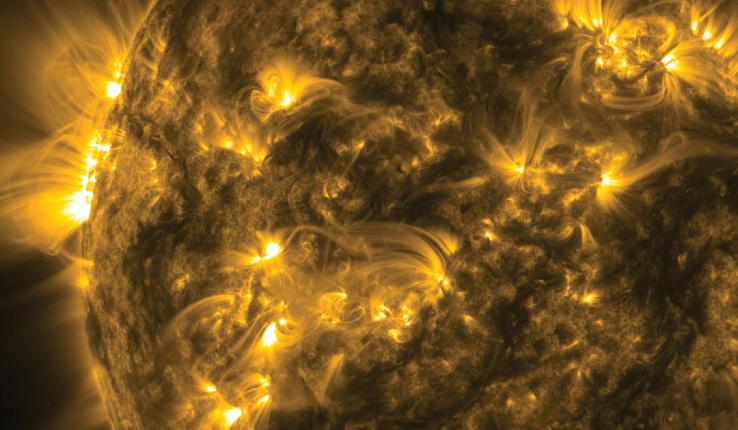

What would it take to meet the world’s energy needs, sustainably, far into the foreseeable future? Perhaps creating energy the way the sun does, through nuclear fusion.

Fission and fusion are very different nuclear reactions, according to Eugenio Schuster, professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics. Fission, which produces the type of nuclear energy created by reactors here on Earth since the 1950s, involves splitting the nuclei of very heavy elements, such as uranium and plutonium, which starts a chain reaction that is difficult to slow—among the reasons it can be dangerous.

Nuclear fusion, on the other hand, is a very difficult reaction to spur and maintain. The sun creates energy—in the form of light and heat—by fusing atoms of hydrogen, the lightest gas, using its massive gravitational force to confine the hydrogenic gas long enough for the nuclear reaction to take place.

On Earth, many scientists believe the most promising path to creating energy through nuclear fusion is one that uses heat to spur a similar reaction. This method combines two isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium and tritium, by heating them up to 100 million Kelvin—approximately six times hotter than the sun's core. The kinetic energy of these isotopes is increased by heating, which allows them to overcome the repulsion force due to the positive charges (protons) in the nuclei and to fuse. Scientists use magnetic fields to confine the resulting substance, which is no longer a gas, but a plasma. The “burning plasma,” as it is known, is confined in a toroidal-shaped apparatus: the tokamak, which is a Russian-language acronym that translates to “toroidal chamber with magnetic coils.”

Schuster, a nuclear-fusion plasma control expert, works on ways to control and stabilize the heated plasma.

“We are plasma dynamicists,” says Schuster, describing the role of researchers like him on the road to making nuclear fusion energy a reality. “What we do is to try to understand the plasma’s dynamics, coming up with equations to model its behavior, particularly in response to different types of actuators. But we don’t stop there. We want to modify the actuation to create the dynamics we want. We want control and stability of the burning plasma.”

Recent work by members of Lehigh’s Plasma Control Laboratory led by Schuster will be presented this week at the 27th International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Fusions Conference in Gandhinagar, India. Their first piece of work, entitled “Physics-model-based Real-time Optimization for the Development of Steady-state Scenarios at DIII-D,” discusses recent experimental results that demonstrate the effectiveness of a model-based real-time optimization scheme to consistently achieve desired advanced scenarios at predefined times. The work was done at the DIII-D National Fusion Facility, housed at General Atomics, a private technology company in San Diego, California.

According to Schuster, the results suggest that control-oriented model-based scenario planning in combination with real-time optimization can play a crucial role in exploring stability limits of advanced steady-state scenarios.

Their second piece of work, entitled “Robust Burn Control in ITER Under Deuterium-Tritium Concentration Variations in the Fueling Lines,” focuses on how to control the fusion power of a burning plasma when unmeasurable variations of the deuterium-tritium concentrations in the fueling line are present.

In this work, in-vessel coil-current modulation is included in the control scheme, and it is used in conjunction with auxiliary power modulation, fueling rate modulation, and impurity injection to design a nonlinear burn controller which is robust to variations in the deuterium-tritium concentrations of the fueling lines.

This controller addresses one of the most fundamental control problems arising in burning-plasma tokamaks, which is the regulation of the plasma temperature and density to produce a determined amount of fusion power while avoiding possible thermal instabilities. A nonlinear simulation study is used to illustrate the successful controller performance in an ITER-like scenario in which unknown variations of the deuterium-tritium concentration of the fueling lines are emulated.

Schuster and his team are engaged in several national and international collaborations and regularly conduct experiments on a number of tokamaks around the world. These include DIII-D at General Atomics, where one of his Ph.D. students and a postdoctoral researcher are permanently stationed; NSTX-U at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey, where one of his former Ph.D. students is playing a leading role in plasma control; EAST in China; KSTAR in South Korea; and ITER in France.

Schuster, one postdoctoral researcher, and four of his Ph.D. students will attend the 60th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Plasma Physics in Portland, Oregon in early Nov., where they will present work arising from these collaborations.

Schuster Named ITER Scientist Fellow

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) is a nuclear fusion tokamak being built in Southern France as the result of an unprecedented cooperative effort by governments around the world. It is a global collaboration that aims “to build the world's largest tokamak, a magnetic fusion device that has been designed to prove the feasibility of fusion as a large-scale and carbon-free source of energy based on the same principle that powers our Sun and stars.” The ITER Project is a collaboration of 35 nations, led by ITER members: China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the United States.

Schuster, who is currently serving as Leader of the Operations and Control Topical Group within the U.S. Burning Plasma Organization (BPO), was recently named to the prestigious ITER Scientist Fellows Network designed to strengthen the involvement of the fusion community as ITER prepares for its operational phase. The ITER Scientist Fellows Network members work closely with each other and ITER to address key research and development issues.

The U.S. Department of Energy also named Schuster as a member of ITER’s Integrated Operation Scenarios Topical Group within ITPA: International Tokamak Physics Activity (ITPA). The scope of the Integrated Operation Scenarios Topical Group is to contribute to establishing operational scenarios in burning plasma experiments, particularly candidate scenarios in ITER.

“Currently, nuclear fusion reactors do not produce energy,” says Schuster. “The experiments done on tokamaks around the world are focused on studying the physics of the plasma.”

ITER is looking to be the first tokamak to produce net energy via nuclear fusion efficiently enough for the reaction to be sustained for a long duration—and become a reliable energy source. The goal, says Schuster, is to produce ten times more energy than is injected into the tokamak.

Though researchers have been trying to realize nuclear fusion’s promise for more than sixty years, Schuster believes they might be getting much closer. ITER’s first plasma is scheduled for 2025.

“Unlike fossil fuels, nuclear fusion produces no air pollution or greenhouse gases,” says Schuster. “Unlike nuclear fission, nuclear fusion poses no risk of nuclear accident, no generation of material for nuclear weapons, and low-level radioactive waste.”

In other words, the work that Schuster and his colleagues are doing at ITER and other facilities could help bring us closer to a carbon-free, combustion-free future where the world’s energy needs are met by a near-limitless source—like the sun.

Posted on: