Eye-tracking cameras allow researchers in the field of psychology to measure changes in a subject's eye movements and analyze how they process visual information. Eugene Han, an assistant professor of architecture, takes a different approach.

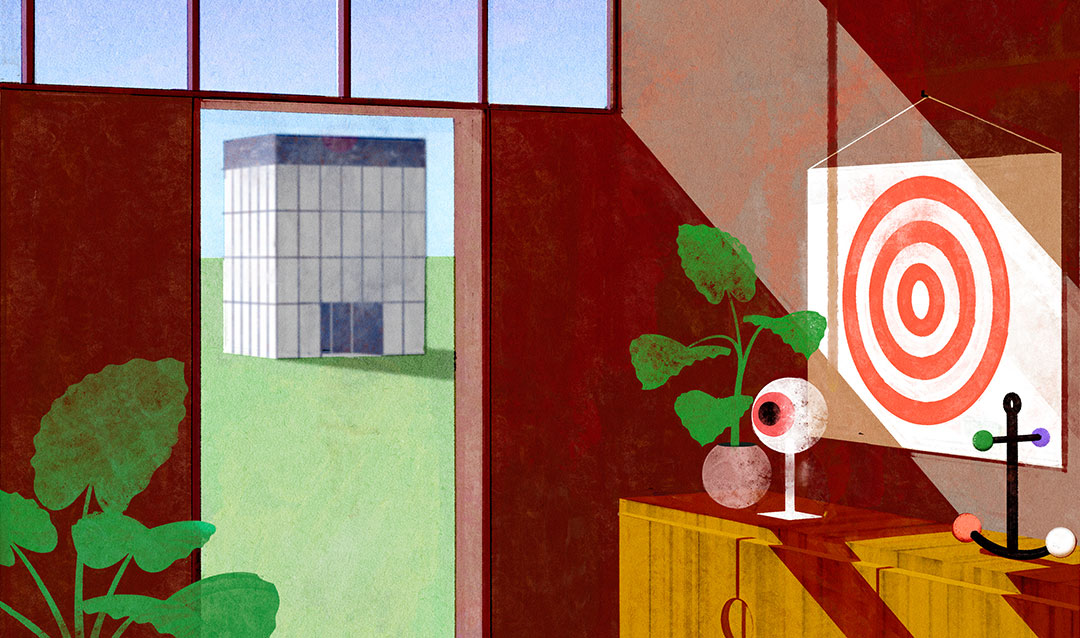

Han uses the cameras as a creative tool to analyze eye movements and visualize the different ways people see art and architecture. His eye-tracking studies have explored in a variety of ways how people look at, for example, images, sculptures and passages through building complexes.

“My focus certainly is not about discovering generalities or what makes our minds work. That's definitely an interest, but at the end of the day, mine are design projects. I think everyone has something to say and to contribute with how they see,” he explains.

Han’s exploration of perception and eye tracking was born of coincidence—one that allowed him to merge his technical interest in eye-tracking cameras with his historical interest in aesthetic perception. While a doctoral student at Yale, he purchased a low-cost device for tracking eye movement and tested its efficacy on his students. Around the same time, the writings of 19th century German art theorist Konrad Fiedler and his peers inspired Han to analyze the role of visual perception in aesthetics.

“[Fielder] spoke quite heavily about the role of perception, how in aesthetic theory we needed to include the process of seeing, the act of seeing—[that] it wasn't immediate and it wasn't the same for everyone,” he says.

In one of Han’s studies, cameras track participants’ eye movements in a darkened room as they view a series of images. He uses a triangulation method to measure and map where each subject looks while viewing each image or object. Once he has that data, Han writes programs to develop two-dimensional visualizations that represent his findings.

His current work involves mapping eye movements within spaces. In this study, participants wear an eye-tracking device connected to a cable. Han maps where they look as they walk around a space and in three-dimensions.

“Tracking people's perception of spaces goes back to the basics of architecture,” says Han. “As opposed to an image that's projected on a monitor in a darkened room, when you actually walk through a space that's outdoors, the number of variables are exponential.”

When a person is experiencing a space, ambient conditions such as lighting, temperature and acoustics come to the forefront.

“As an investigator, but also as an architect and a designer, you realize that you can never be in control of all those variables,” Han explains. “The amount of complexity is something you just have to embrace in your buildings. You have to be cognizant of it, but you also have to embrace that people will view and perceive your buildings in very different ways.”

Han recognizes the inherent danger in using tools such as eye-tracking cameras to optimize design. It’s the complete opposite of what he’s trying to do, he says.

“I'm trying to emphasize that, as architects, we should support interactions of our own projects that exceed, go beyond and surprise our own understanding that the creator is not always in control,” he continues.

“I always liken perception to reading. When we look at buildings, we're reading buildings. And in that note, when we think of the word ‘author,’ the word comes from ‘authority.’ And I think there's that danger as architects, we think that we have certain authority in how people should use or perceive or understand our buildings. If anything we just promote [and] provoke manifolds of reading.”