Minister, mastermind and madman

In addition to her fellowship at the Huntington Library, Zepeda Cortés has studied the career of 18th-century Spanish reformer José de Gálvez at the Archivo Saavedra in the Facultad de Teología de Granada in Spain.

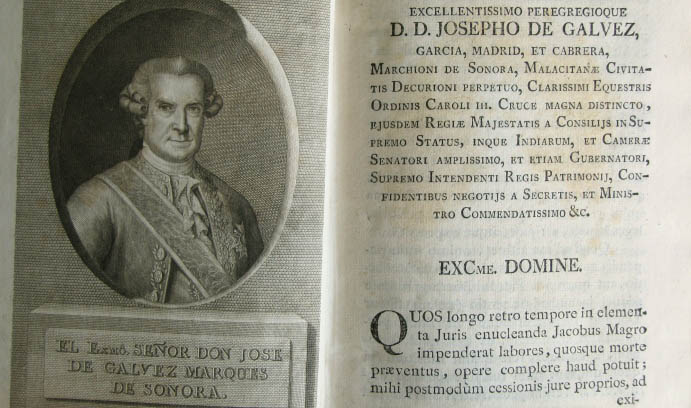

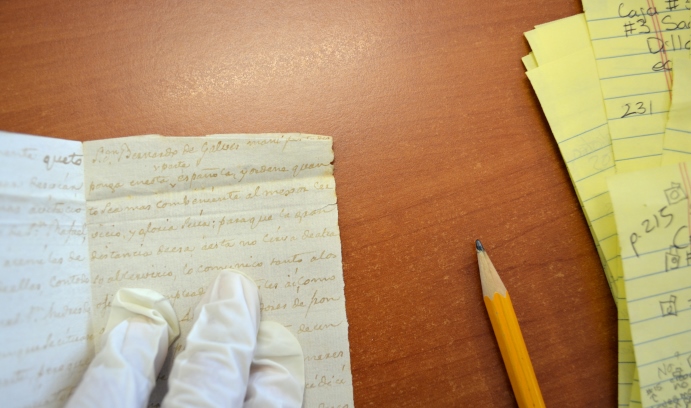

Eleven boxes and two oversize folders hold the 734 documents that comprise “The Gálvez Papers” at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. The collection is the largest in the United States of historical documents related to José de Gálvez, a wildly successful reformer of Spain’s New World colonies (including present-day Mexico) whose influence still resonates today.

The Gálvez Papers consist mostly of correspondence between Gálvez and the viceroy of Mexico, and include a number of documents relating to the settlement of California in 1769. The documents span the period between 1763 and 1794, an era that overlaps with the Bourbon Reforms—named for the House of Bourbon which ruled over Spain and its colonies in the late 18th century. In 1765, as part of these reforms, Gálvez was sent by Spanish King Carlos III to New Spain to stop corruption and strengthen Spain’s rule.

The region now known as Mexico had largely ruled itself from the 16th to the 18th century. According to history professor María Bárbara Zepeda Cortés, Spain had watched while Britain and France expanded their empires and used their colonies to enrich their countries—and now Spain wanted to do the same.

“Though Gálvez came from an impoverished family, he had climbed the political and social ladder all the way to the top,” says Zepeda Cortés. “The King trusted Gálvez to lead these huge, highly political reforms in which Gálvez had to negotiate with entrenched factions within colonial Mexico and face fierce opposition to the control being imposed by the crown.”

Despite considerable obstacles, Gálvez thrived. He made unexpected allies, such as the independent traders who traveled the route between Spain and Mexico. Many of his moves were brazen enough to stir the ire of the viceroy who was charged with overseeing New Spain and whose authority Gálvez continuously challenged.

Gálvez also faced opposition inside the Crown from those who were not happy with the way he conducted reforms. But the King had confidence in him until the day Gálvez died.

Gálvez stayed in the colonies for seven years and, briefly after his return to Spain, was appointed Minister of the Indies, a position of even greater power and responsibility. All issues coming from the Spanish colonies were his to address and some, says Zepeda Cortés, were tough ones.

“For example, there were border issues between Spanish America and Brazil, a Portuguese colony,” says Zepeda Cortés. “In addition, the Crown began imposing state monopolies on the colonies’ most-consumed goods—such as tobacco and alcohol—challenging established producers and creating a lot of distress. Many in the Americas began to see Gálvez—not the Crown—as the source of the reforms.”

“In spite of these thorny issues, he became one of Spain’s most successful reformers transforming potential enemies in the colonies into allies who remained loyal to him and his family.”

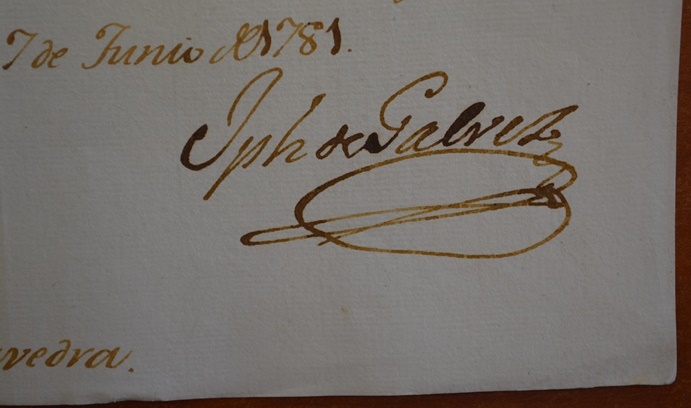

Both during his time Mexico and when he returned to Spain, Gálvez produced a substantial paper trail. According to Zepeda Cortés, Gálvez signed so many documents that near the end of his life a carpal tunnel-like affliction prevented him from being able to sign official papers by hand. The King then granted him special permission to use a stamp.

Despite his impact, the story of José de Gálvez remains underexplored. The last U.S. book about him was published in 1916. Who was this man whose legacy has shaped the western United States, Mexico and parts of South America?

Zepeda Cortés will spend 10 months searching “The Gálvez Papers” for answers. She won a prestigious long-term fellowship to study at The Huntington Library. The Barbara Thom Postdoctoral Fellowship is designed to support non-tenured faculty who are revising their dissertation for publication. Zepeda Cortés’s book is tentatively titled: The Politics of Reform: José de Gálvez and the Transformation of the Spanish Empire.

One of the reasons for her interest in Gálvez, says Zepeda Cortés, is that historians have tended to focus on other Spanish ministers. Zepeda Cortés is also fascinated by some of the more outlandish stories surrounding him.

For example, in an attempt to colonize California, Gálvez led a military expedition to Sonora (now in the northwest region of Mexico) where a group of indigenous people were organizing regular attacks on Spanish settlements. He and his army lost.

“For six months, he went crazy,” says Zepeda Cortés. “There are reports that he would run around naked calling himself Montezuma—an Aztec emperor—and that he once told his troops that he was going to send monkeys in uniform to fight the next battle because his own soldiers were incompetent.”

She is also interested in how his interventions changed the region “in surprising ways.”

Gálvez empowered regional leaders, shifting power away from the viceroy. Many of the regions he carved out eventually became the federal states Mexico, as well as the provinces of Argentina and Peru. His nephew, Bernardo Gálvez, became a hero of the American Revolution when he led Spanish forces to defeat the British in the Siege of Pensacola. Bernardo later became Governor of Louisiana. The city of Galveston, Texas, is named for him.

Another example of Gálvez’s impact: Before the Bourbon Reforms, the colonies did not have standing armies. During Gálvez’s time, militias were created to defend against Spain’s foreign enemies in the region—such as Portugal and Britain.

“Those armies were largely made up of locally born men of Spanish descent known then as Criollos and, later, Mexicans or Americanos,” says Zepeda Cortés. “Those armies became the rebels and eventual supporters of the Latin American wars for independence.”

The Huntington Library archive contains letters, documents, and one map (all in Spanish) which were assembled in 1794 for the second Conde de Revillagigedo. Official correspondence (1765-72) between Gálvez and the successive viceroys of Mexico deals with the organization of expeditions sent to San Diego and Monterey to occupy California, the efforts to enlarge the frontiers of New Spain and subdue the Indians in Sonora and Sinaloa, and the removal of the Jesuit missionaries from Lower California.

According to The Huntington Library’s website, 1,700 scholars come from around the world every year to conduct advanced humanities research using The Huntington’s collections. Through a rigorous peer-review program, the institution awards approximately 150 fellowships to scholars in the fields of history, literature, art and the history of science.

Story by Lori Friedman

Photos courtesy of Bárbara Zepeda Cortés

Posted on: