LU Philharmonic Performs Mahler’s Sixth

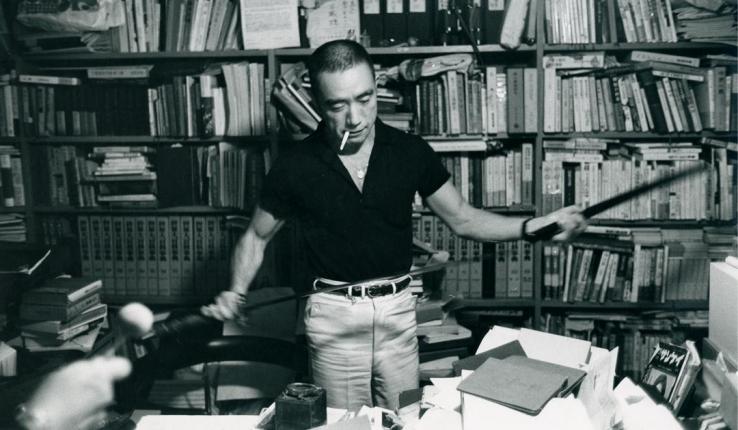

The Lehigh University Philharmonic performed Mahler’s Sixth Symphony and the Emperor Waltz by Strauss in December in Baker Hall. (Photo courtesy of Eugene Albulescu)

Gustav Mahler’s Sixth Symphony has been called “the Tragic Symphony,” but the massive work was actually written during one of the happiest periods of the composer’s life.

Mahler had been married in 1902, his first daughter was born later that year and his second daughter was born as he completed the Sixth Symphony in 1904. The tragedies that marked his final years did not begin until 1907, when his older daughter died, and he was fired as director of the Vienna Court Opera and diagnosed with what proved to be a fatal heart ailment.

The Lehigh University Philharmonic performed Mahler’s Sixth Symphony in two concerts in December in Baker Hall of the Zoellner Arts Center. The four-movement work lasted approximately 90 minutes. The orchestra also performed the Emperor Waltz by Johann Strauss.

Eugene Albulescu, the orchestra’s director, believes the Sixth Symphony is more a commentary on the times than a reflection of the events in Mahler’s life.

“The Sixth Symphony is not so much autobiographical as it is a reading of the times and of music history,” says Albulescu, who is now in his 10th season as the orchestra’s leader and who is also the R.J. Ulrich Endowed Chair in Orchestral Studies at Lehigh.

“This period of time represented the end of an era. The Sixth Symphony was the last great Romantic symphony, and it was the crowning of the Viennese tradition; it embodied traditions starting with Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms and Bruckner.”

The Sixth Symphony “quotes” liberally from the works of earlier composers, says Albulescu, incorporating well-known motifs and melodies from Schubert, Liszt, Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov.

“To me,” he says, “the Sixth Symphony feels like an end to a chapter that includes musings on music history and musical traditions. Mahler challenged those traditions and moved them further—possibly too fast for Viennese society of his time.”

The Lehigh Philharmonic’s performance of the Sixth Symphony will feature 100 musicians on stage. The orchestra, which includes students, faculty, staff and community members, retained the services of several additional brass and woodwind players for the performance, says Albulescu.

For the orchestra members, especially the student contingent that makes up 60 to 70 percent of the ensemble, Mahler’s Sixth Symphony represents an “aspirational piece” that has required musicians to practice their parts outside the three-hour weekly rehearsal, says Albulescu. In recent years, the orchestra has taken on similarly challenging masterworks, such as Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony and Shostakovich’s Seventh “Leningrad” Symphony.

“The Lehigh Philharmonic is a wonderful group,” says Albulescu. “They can do amazing things. The students are in increasing reverence and awe of the repertoire we do. Mahler was one of the most consequential artists in the history of classical music. You can’t be nonchalant about this symphony.

“I’m very happy with how the orchestra is evolving. We are able now to do a lot of artistry and focus on a conception. I send the musicians YouTube links so they can hear how other orchestras have played the pieces they’re playing. In this way, they realize that getting the notes right is just the first step; after this, we need to coalesce as a group and ask ourselves what our take on a piece is. That’s the key element.”

One of the more dramatic moments in Mahler’s Sixth Symphony comes late in the final movement when a percussionist strikes a large wooden box two times with a hammer. Mahler instructed that the sound be “brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character.”

“Some people have said that they think the striking of the box foreshadows the trajectory that Mahler’s life would take,” says Albulescu. “Others have compared it to the blow of fate. I think that’s a bit of baloney.

“For me, the hammer is the symbol of the end of an era, the end of the aesthetic of beauty and symmetry and a sensibility that was based on equilibrium. It’s the symbol of something entirely new, of uncharted territory.

“This is the last great Romantic symphony, and it finishes in grand style with a new instrument that isn’t really a musical instrument.”

With help from the scene shop of Lehigh’s theatre department, Albulescu and members of the orchestra constructed what they call a “Mahler box” that is shaped like a cube and stands about 4 feet tall. Albulescu is confident that the group met their main challenge—to make the box strong enough to withstand more than one blow but not so strong that it muffles the reverberation from the blows.

“I’m into building things,” he says. “I really like building orchestras.”

Posted on: