Jesse Pomeroy: Making a Monster

Jesse Pomeroy was 12 years old when he began torturing other young boys. Later, at 14, he murdered two children, just before Jack the Ripper terrorized London and H.H. Holmes preyed on victims at the Chicago World’s Fair.

Holmes is considered America’s first serial killer. But, says Dawn Keetley, Pomeroy brought the notion of the modern serial killer into the public eye.

“He was the first person who compulsively killed total strangers for no reason. ... His was the crime of the century in 19th-century Boston, not least because he was so young,” she says.

Keetley, professor and chair of the English department, examined newspaper articles, letters, legal documents and written transcripts to write a book about Pomeroy’s life and crimes. Making a Monster: Jesse Pomeroy, the Boy Murderer of 1870s Boston was published in 2017 by University of Massachusetts Press.

The “whys” of the case of Jesse Pomeroy most interested Keetley. “He said things that tried to articulate some sort of compulsion. … He was kind of helpless in the face of this compulsion and that really interested me about the case. Where did that compulsion come from?”

Keetley disagrees with the most widely accepted explanation of Pomeroy’s crimes: that he was abused by his alcoholic father. Although the family was not stable, she says, there is no evidence that Pomeroy’s father abused him, and they maintained a relationship after he moved out of the house.

“I think [abuse is] our go-to explanation for severe pathological problems, especially in young children,” she says. “And I just don’t think that’s true in this case. … It just taps into the familiar story rather than looking at the facts and figuring out what’s the real story, not just what confirms what we already think happened to Jesse Pomeroy, but what actually happened.”

Keetley reveals in Making a Monster a different—and somewhat unexpected—explanation for Pomeroy’s psychopathy: a bad reaction to a vaccine he received as an infant during a smallpox epidemic in Boston. Following his vaccination, the boy’s entire body became covered with blisters and abscesses for months, leaving him in a state of constant pain, unable to be touched or held during a critical time of child development.

“[Infants] need to be held, to be comforted, to form an attachment with a caregiver,” says Keetley. “My theory is that none of that happened [and] that caused his psychopathy. He had no empathy, really no interior life at all. He was unable to form bonds with people.”

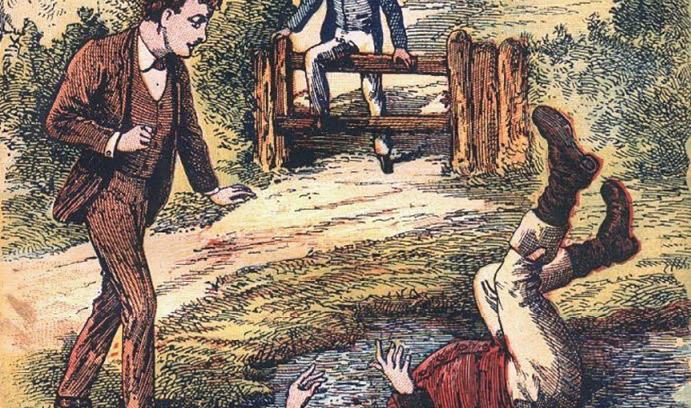

Pomeroy’s heinous acts were likely also influenced by torture scenes depicted in the western dime store novels he liked to read, Keetley says. His actions, described in the testimonies of the seven boys he tortured, “really echoed the torture scenes in dime novels, which were mostly about Native Americans capturing white frontier settlers and torturing them in various ways: tying them up, sticking them with knives and pins, dancing around them, scalping them. All of these things—all of them—Jesse Pomeroy tried to enact on his victims.”

Despite the horror of his actions, though, Keetley says, society too easily dismisses people like Pomeroy—those who commit monstrous crimes—simply as monsters. They are, after all, human beings.

The story of Jesse Pomeroy, she writes, “teaches us to avoid casting others as absolute monsters, casting them outside the human community. When you scratch the surface, the bonds between ‘us’ and ‘them’ are strong.”

This story appears as "Making a Monster" in the 2018 Lehigh Research Review.

Posted on: