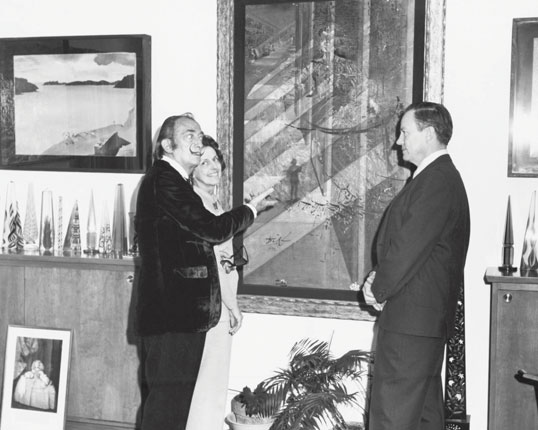

What hung on Brad Morse’s bedroom wall as a teenager: a poster of Ted Williams at Fenway Park or surrealist Salvador Dali’s renowned Nature Morte Vivante oil painting?

It couldn’t possibly be choice number 2, one might say, given that so many of Dali’s paintings are priceless. (The winning bid on Dali’s Portrait de Paul Eluard was $22.4 million at Sotheby’s London auction in 2011.) But surprise: Choice number 2 is correct.

Morse, who graduated from Lehigh in 1965 with a degree in mechanical engineering, says Dali’s original Nature Morte Vivante (Still Life–Fast Moving) had been so close to the side of his bed growing up that the headboard’s upholstery tack wore a groove in its frame.

The 49-inch-by-63-inch painting can now be seen by the approximately 450,000 visitors each year to the Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Fla., which was built to house his parents’ Dali collection of more than 2,000 objets d’art, including nearly 100 paintings, 1,000-plus drawings, watercolors, prints, films and designs for clothing, furniture and ballet sets.

Morse serves on the museum’s executive committee of the board of directors. Despite his weak color vision, not uncommon in men, Morse says he enjoys strolling through the museum admiring the artworks that had covered, floor to ceiling, the walls of his childhood home near Cleveland, Ohio. It was his parents’ hope that their collection remain intact.

“That dream has been realized,” Morse says, “and that’s really very satisfying, that they were able to not only collect the art, but find a way to give it a home.”