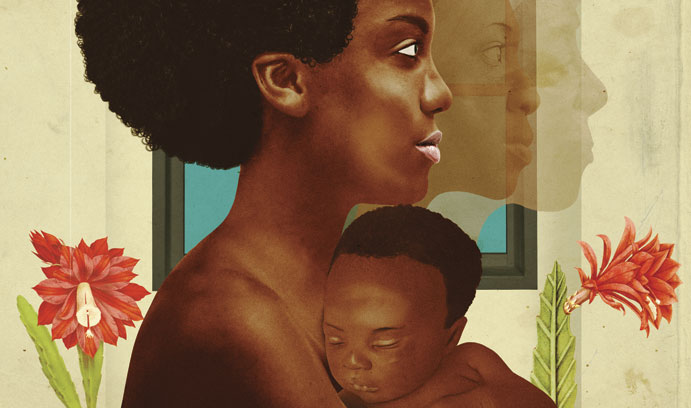

Encouraging Maternal Attachment

Susan Woodhouse is using a $2.1 million grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to investigate which behaviors among mothers can help foster a safe and secure attachment to their infants.

Susan Woodhouse challenges some long-held beliefs about maternal attachment.

Through a five-year, federally funded research project, Woodhouse, associate professor of counseling psychology, is investigating which aspects of mothers' caregiving for their babies best predict children's security of attachment, ability to regulate their emotions, and early indicators of mental and behavioral health. In an earlier study, Woodhouse found that in racially diverse and low-income families, a mother's sensitivity does not appear to be a key predictor of secure attachment.

Most prior research in this area has involved primarily white, middle-income families. Woodhouse instead studies low- income mothers of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. She found among them many mothers whose babies feel safe and secure, in spite of what might appear to be insensitive parenting styles.

"Clearly, there is a gap in our understanding of what parenting behaviors really make the most difference in promoting a secure attachment," says Woodhouse. A $2.1 million grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, one of the federal government's National Institutes of Health, supports her quest to find answers and close that gap.

The grant, titled "Caregiving, Attachment, and Regulation of Emotion," or CARE, allows Woodhouse to observe 200 primarily low-income women and their infants at 6 months and 12 months of age to determine what behaviors lead to a secure attachment, as well as the actions that detract from such attachment. In addition, Woodhouse examines other important child outcomes, such as early signs of behavioral problems as well as physiological indicators of how babies react to and recover from stress and how babies manage their emotions and focus their attention. All of these are important outcomes in terms of later school readiness and mental health.

"We hope to learn what Mom behaviors make the most difference in predicting baby outcomes," says Woodhouse, the study's principal investigator. "If we want interventions that work when there are limited resources, we want to focus on what matters most."

Understanding infant security

Woodhouse began the study in March 2012 as a faculty member at Pennsylvania State University and continued when she arrived at Lehigh later that year. More than 100 mothers and babies have enrolled so far, and Woodhouse has begun to analyze the data she's already collected. She concentrates on the simple but powerful act of a mother holding her child "chest-to-chest" to calm the infant's crying.

"My new discovery is the key importance of chest-to-chest soothing when infants cry," says Woodhouse. "Even if a mother is making a lot of mistakes and being insensitive along the way, as long as she finally relents and comes through in the end by soothing the baby chest-to-chest, that baby will be secure. She doesn't even need to do it every time. As long as she does it at least 50 percent of the time, that baby will still be secure."

In fact, even if a mother does not hold her child chest-to-chest at least half of the time the child cries, her baby can still feel secure if the mother displays what Woodhouse calls "calm connectedness." For example, babies were secure if their mothers returned their gaze or if their mothers carried them while attending to household tasks.

CARE has also allowed Woodhouse to assess findings from her prior research that identify parent behaviors that negatively affect secure attachment. Frightening children in an attempt to stop them from crying, for example, proved ineffective. Woodhouse found that some year-old infants were unable to feel secure after their mothers had scared them by shouting or lifting them repeatedly into the air. Although the child stops crying, there are later negative consequences for the child in terms of disorganization of attachment, which is associated with later behavioral health problems.

The impact of stress

Each participant must have a child 6 months of age or younger who is not yet crawling. Woodhouse and her team have been enrolling women at community events, housing projects, child-care centers and clinics. Team members distribute brochures to anyone who might qualify and explain that they're studying "how mothers and babies deal with everyday feelings and stress that are a normal part of raising healthy children." Researchers observe and test mothers and babies in their homes and in a lab-playroom, which offers a comfortable couch, age-appropriate toys and two cameras mounted near ceiling corners.

During the first two-hour visit, when the baby is 6 months old, researchers check heart rates and swab mouths for the hormone cortisol to assess stress levels of the mother and baby during normal tasks, such as strapping a child into a car seat.

The ability to adapt to stress and regulate emotions is key in later mental health and school readiness. By watching how babies' cortisol levels rise after a simple stressor and then how quickly this stress hormone returns to normal, Woodhouse can gauge whether a good mother-baby relationship buffers children from the negative effects of stress.

Because babies' heart-rate variability is an important marker of infant emotion regulation, electrocardiogram (EKG) wires are attached to the mother and child and tucked into a backpack or vest to avoid hampering movement during mother-baby interactions.

Researchers also observe behavior in the family home three times over two weeks by videotaping the mother and child for 30 minutes during everyday activities. When the baby is 12 months old, the mother brings him or her back to the lab for another two-hour testing and observation session. That's followed by two at-home observations, each 1.5 to 2 hours in duration, a week apart. CARE staffers are trained in how to videotape and rate the behaviors they observe.

After they complete the testing, participating mothers are offered social services, as well as parenting support through a program Woodhouse considers one of the most promising interventions available. The program, "Circle of Security," uses a video to stimulate learning and discussion about infant needs. By playing a game called "Name that Need," mothers learn whether a baby needs to be soothed or encouraged to explore. In addition, mothers are supported in exploring how to better meet their own babies' needs.

'The results belong to the community'

Woodhouse participates in a community-research partnership called Parents and Children Together (PACT). As a PACT member, she receives guidance and suggestions from a PACT Community Advisory Board, which includes community leaders and grassroots community members, about how to best engage the community. It was the Community Advisory Board's idea, for example, to give mothers parenting support at the final visit.

"They wanted to make sure each mom would immediately get something positive to support her parenting, in addition to contributing to building knowledge about mothers and babies in the community," says Woodhouse, who regularly reports back to community members about her findings "so that the results belong to the community, not just to the scientific community."

Denise Sturnes, project coordinator and lab director, says she's seen mothers enter the study not knowing what to expect and later leave with a greater awareness of how to connect with their infants. "It's been rewarding for me to see the transformation," she says of mothers who learned that their children were not trying to bother or irritate them, but were instead in need of comfort and love.

Woodhouse says she understands that many other factors can influence a child's development, including behaviors of the father, grandparents and other guardians. However, mothers remain the primary caregivers of children around the world.

"For the first time, we are starting to see some of the hidden strengths that exist in low-income moms," Woodhouse says. "As we figure out what matters most for babies, we can develop interventions that will build on those existing strengths. We can help moms who are struggling look more like the successful moms within their own communities instead of trying to make them look like other moms from other places."

Kristin A. Buss, who directs PACT and is professor of psychology and director of graduate training at Penn State, considers Woodhouse's work "innovative."

"First, the work is innovative in the focus on specific aspects of mothers' behavior that help babies form secure attachment," says Buss. "The conceptual idea is that when mothers, regardless of cultural variations which have historically been viewed as maladaptive or less sensitive, engage in behaviors that help the baby calm, even if that behavior doesn't look pretty, it is effective. The second thing that sets CARE apart is that when families are done with the study, they enter an intervention phase."

Buss says the impact is not likely to happen overnight, but hopefully families in the study will see benefits from the lessons, and PACT members can help disseminate the findings in the community. Woodhouse anticipates completing the study by February 2017.

New Discoveries

Woodhouse and doctoral student Netta Admoni recently analyzed preliminary data from the CARE study regarding CARE heart-rate variability data, an index of parasympathetic nervous system activation, as mothers and babies move through a task similar to what happens if a mother interrupts playing with her baby to take a phone call. Mothers spend three minutes engaging in face-to-face play with the baby and then look away with a neutral face for two minutes before finally reengaging normally with the baby. Findings suggest that mothers who provide higher-quality caregiving have infants who seem more comfortable with their mothers disengaging for a couple of minutes. In contrast, mothers who provide lower-quality caregiving have infants who show physiological signs of stress when mothers look away and then show signs of greater stress, on a biological level, when their mothers reconnect with them. Woodhouse’s lab is the first to identify different changes in babies’ heart-rate variability depending on quality of care.

Susan Woodhouse is an associate professor of counseling psychology whose research interests include attachment, emotion regulation, parenting, prevention and psychotherapy. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Maryland at College Park.

Illustration by Laurindo Feliciano

Posted on: