Fink read Fanon’s book, an analysis of the dehumanizing effects of colonization. She thought: What does this mean for the type of research we are doing on PTSD? What does it mean for treating a person with PTSD in a similar violent, dehumanizing context today?

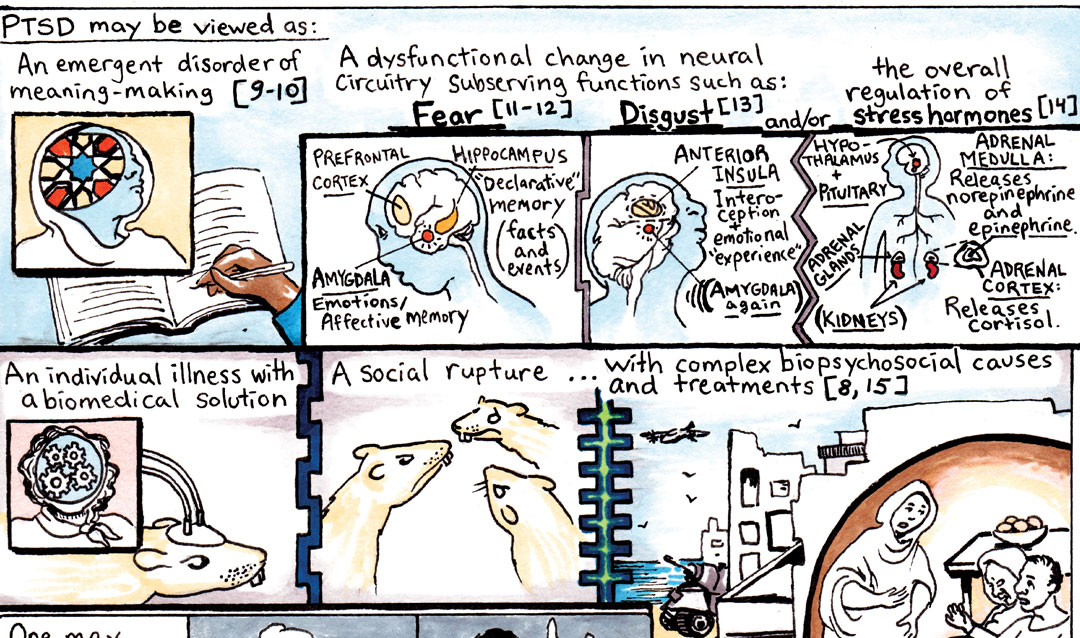

Fink chose to present her bioethical inquiry in comic-book form because a lot of what she wanted to convey was so visual. She is part of a growing movement known as Graphic Medicine, a term that refers to academics and clinicians who believe that comics are a compelling way to engage in health care discourse, especially around complex subjects.

While the scenario presented in the case study would be considered unacceptable and unethical by current frameworks, Fink writes, it raises the question: “Is it possible, in a colonized Algeria struggling for its national sovereignty, to treat the European police inspector in a meaningful way?”

She writes, “What are the responsibilities of clinicians treating such traumatized individuals? Of researchers who define the biomedical boundaries of traumatic stress? What particular rights apply to people suffering from PTSD, and for what actions can they be found culpable? Finally, what collective social responsibilities arise from understanding trauma, and how might researchers and clinicians weigh these against responsibilities to the individual?”

Fink illustrates the possible paths that Fanon could have chosen to treat his patient’s PTSD—one that allows the inspector to return to his job as a torturer, another that stops the inspector’s abuse of his spouse and children. Each path carries an inherent prioritization of some individuals’ suffering over others: the inspector, his wife and children, for example, or the Algerian victims of his torture? The inspector himself is drawn as having two distinct roles, as ill person and perpetrator.

At the conclusion of the paper, Fink writes, “...the analysis of PTSD presented here entails moral obligations for practitioners of neuroscience that extend beyond the laboratory or clinic: To address, at its root, the political, gendered and racialized violence that represents the overwhelming causal factor in disorders of traumatic stress. To refuse to support or participate in practices that exploit and brutalize individuals and entire cultures. To social change that prioritizes these commitments.”

Fink acknowledges both the difficulty and importance of confronting these issues. “It is a call for people to think carefully about how they do research, how they write about it, how it’s applied, how they talk about identity,” says Fink. “Until recently, those in neuroscience didn’t have to be very socially conscious. ... But researchers must develop that kind of critical consciousness. It is a call to clinicians as well to grapple with these issues.”