A writer’s notebook

Revision, says Johnson, National Book Award-winning author of Middle Passage, accounts for 90 percent of good writing.

Charles R. Johnson, novelist, cartoonist, author of 22 books and professor emeritus of English at the University of Washington, delivered the baccalaureate address for Lehigh’s 148th Commencement on May 22. In 1990, Johnson won the National Book Award for Fiction for his first novel, Middle Passage. He has also received a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. A Buddhist and a student of Sanskrit, Johnson holds a Ph.D. in philosophy from SUNY-Stony Brook. While visiting Lehigh, Johnson held a conversation with Kurt Pfitzer of the office of university communications.

When you won the National Book Award for Fiction in 1990, you paid tribute to Ralph Ellison, author of The Invisible Man and one of the most influential American writers of the 20th century. Like Ellison, you have said that writers should make the invisible visible. How long did you spend doing research for Middle Passage to accomplish this?

I first did a version of Middle Passage in 1971 when I was an undergraduate. It was too early in my career to get it right, so I put it aside and continued doing research on the slave trade. I started the final version of Middle Passage in 1983 and worked on it until 1989. For six years I studied what I didn’t know because I’d never been to sea. I’d never been on anything except a ferry boat on Puget Sound. So I read ships’ logs and slave narratives that had something to do with the sea. I worked on understanding the literature of the sea. I read all of (Herman) Melville, not for plot but for props and costuming and the language of the sailors. I read (Jack) London, I read the Sinbad stories, I read Apollonius of Rhodes, I read nautical dictionaries.

I had a neighbor at the time, Gene, who built ships for the government; he built a model for the Navy of one of their boats. Gene built me his version of a slave ship that I had as a kind of meditation object during the latter years I was working on the novel.

You also studied the Cockney dialect that was spoken then by many sailors—

I read one book on that. It was fun; it was an obscure academic work in the University of Washington Library. Every book I write is a learning experience. By immersing myself in the language of the sea, I think I got a better appreciation of how much that language is a part of our daily discourse. We say ‘the wind was at my back’—this is nautical language. For a writer, once you get into the language and grammar, you find metaphors and similes that you wouldn’t have thought of before.

The action in the book takes place almost 200 years ago. Are there aspects of it that shed light on the current state of black-white relations in America?

I think so. It has history, Middle Passage, but it’s really a philosophical novel. But the characters, I hope, speak to contemporary readers. Some of their issues are very important for us today. I think in the case of Rutherford (the protagonist), one of his issues is that he never knew his father and only later, through a very supernatural experience on the slave ship, does he find out what happened to his father and why he disappeared.

You have said your own father was a strong figure.

I had a very strong father. He was a very religious man, a quiet religious man who rose to the occasion [in fulfilling] his responsibilities as a father, as a husband, as a brother, as a son to his own father. I’ve been a son and I’ve been a father and now a grandfather. I do think the contribution that fathers make in the lives of children, boys and girls, can be very important.

Tell us about your novel Dreamer (1998), which explores the last two years of the life of Martin Luther King Jr.

Dreamer is the only novel in which King is a character. It’s about a man who was trained to be his double during the Chicago campaign (the Chicago Freedom Movement of 1965-67, also known as the Chicago Open Housing Movement). That was King’s only Northern campaign. I’m from Evanston, Illinois, and I remember when King was in Chicago my senior year of high school. I wanted my novel to be not only a celebration of King and the civil rights movement, but also a celebration of the vision of King, which was very Christian; after all, he was a theologian. So the language of the novel draws in many places from 2,000 years of the work of Christianity.

What kind of research did you do for Dreamer?

I spent two years studying before I even wrote a word. I listened to all of King’s sermons, and read all of them. I read biographies of the man and critical studies of him as a theologian. I read King’s papers; the first 2 volumes were just coming out at that time. I went to his birth house in Atlanta and took the tour. Then I went to the Lorraine Motel so I could see where he was killed. I spent two years immersed in King before I felt confident enough to compose the passages in Dreamer… after two years I felt very confident that I had a sense of how he thought, how he spoke.

You know, if you’re a writer, you have to ask all these questions if you’re creating a character. How does he eat his soup? How does he put his clothes on? What is his favorite meal? Because the historical record on King is so thorough, there are answers to all these questions. But I had to sink into two years of study. And then it became seven years because I was still studying as I wrote the novel.

After Dreamer, I did a text and photo book with the late photographer Bob Adelman, called King: A Photobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., which came out in 2000. That’s one of my favorite books because I was able to deploy the things I had learned about King to trace his history from childhood to his death.

In one interview, you spoke of the ratio of “throwaway pages to keep pages.” Does this ratio improve as you get older?

You write faster as you get older. My teacher, (the novelist) John Gardner, said something along the lines of, ‘When you get older and you’ve been writing a long time, you go faster because you don’t make the mistakes that you made before…and you know strategies and ways of doing things that you didn’t know when you were in your 20s.’ Some of that’s true, but if you’re doing something that’s never been done, or exploring a subject that you have never explored before, you’re still working in a tentative way. You’re still trying this out, trying that out, so the ratio of throwaway to keep pages can be 20 to 1.

To me, that is not surprising at all for literary fiction, because 90 percent of good writing and great writing is revision. It’s rewriting. That’s the fun part of the process for me.

So you’re more of a Beethoven than a Mozart?

Is that the way it worked with those two? Beethoven rewrote a lot and Mozart didn’t? (Sighs) Well, I’m certainly more in the Beethoven mold. Writers are different, though, in their working habits.

Do you sit down to write at a certain time every day?

Nope. Nope. I’m a binge writer. If I’m working on something, I work on it day and night until it’s done, which is usually about two weeks for a short story. I focus on that to the exclusion of anything else. I don’t punch in and punch out. I have to live a story, I have to live with the characters; they’re in my head. I’m walking around all day thinking about them and hearing spontaneous scraps of dialogue and writing them down. I have to do that for a short story.

Now if you’re talking about a novel; that takes six years, seven years. You can’t binge for long. You’ve got to back off and then you come back to it, and so forth.

What other writing tools do you use?

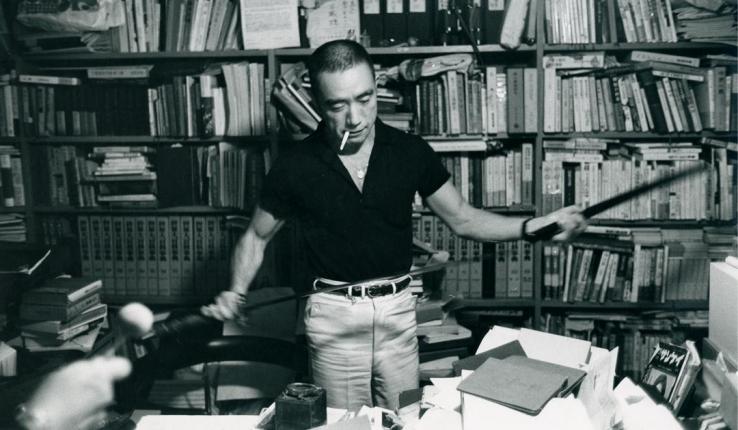

I rely a lot on writer’s notebooks. I’ve been keeping writer’s notebooks since 1972. They sit on my bookshelf. I take notes on dialogue, on speech, and put something in a notebook almost every day. When I go through my notebooks, I can find a word or phrase or thought that I might have had in 1975 that is perfect for the piece I’m doing now. So I go through the notebooks all the time as a memory aid.

I remember I was in San Francisco once. I was on the road doing interviews, and I was in a hotel, and a thought came to me in terms of how Captain Falcon (a character in Middle Passage) ate his dinner. I had just ordered dinner, and I was sitting there ready to eat, and I thought, ‘Oh, this is how Falcon would have eaten.’ So I wrote that down on a piece of hotel stationery, and when I got home, I put it in a writer’s notebook.

You’re a practicing Buddhist, right?

I hope so; I don’t know how good my practice is sometimes.

What kind of wisdom would you share from a Buddhist standpoint with students preparing for life after college?

I really don’t like to say ‘Buddhist’ because that’s a label. Fundamentally, the Buddhist experience, as I understand it, is just the human experience—that’s all. It’s just 2,000 years of teaching and wisdom that we call the dharma, and there’s a community of people who practice those teachings who are called the sangha, and the teacher, of course, is the Buddha. These are the three tools.

What can students get from Buddhism? I’ve written two books about Buddhism. As an old academic, I can say it’s always good to study other cultures than your own; you will be enriched by that. And of course that’s true of other religions as well—Buddhism, Taoism, Judaism, Islam. You want students to be open to the richness of our cultural inheritance, which includes the great religions and spiritual traditions.

On a personal level, I would say that Buddhist practice will help any individual, young or old, understand the operations of your own mind and will help you control your own mind so it serves you rather than runs out of control. I would say the practice of meditation is important for every person on the planet. Right now, there’s a big push for something called mindfulness. It’s like TM in the ’60s; in the ’60s, people took transcendental meditation out of Hinduism. But they took the technique without taking the rest of the religion.

The mindfulness movement does the same thing. It’s taught to CEOs, it’s taught to hedge fund managers, it’s taught to soldiers, it’s taught to everybody as a way of understanding your own thoughts and feelings. And it’s a wonderful thing; it’s taken out of Buddhist dharma because mindfulness is actually part of the Eightfold Path. But the Eightfold Path is an ethical program. All eight parts reinforce each other, they make you lead a moral life, a moral, ethical life, and if you’re not doing that, then mindfulness is not going to work the way it should. You can be mindful as a sniper and very calm as you target your prey—is that what we want mindfulness to be?

I believe meditation should be taught from kindergarten all the way through high school, and particularly when puberty hits and the emotions are raging in young people. Being able to sit and focus their minds would be a very valuable thing, not just for teenagers but for anybody in a moment of stress in their lives or emotional turmoil or tumult. The ability to quiet the mind (helps us) understand that we are not our thoughts and feelings. I experience anger, but I am not anger. I can act on thoughts and feelings in a way that will, hopefully, reduce suffering in the world.

How long have you been a Buddhist?

I first meditated when I was 14…I was a cradle Christian; my parents were Methodist, African Methodist Episcopal, and all my relatives and their kids were raised Christian, and my grandson goes to church every Sunday with my wife, who is almost like a Christian scholar.

When I was a teenager, when I’d come across a Buddhist poem, a haiku, or when I’d see Buddhist art, it would stop me cold. Or I’d come across a line from one of the sutras, and it would stop me in my tracks, and I would say, ‘By God, I think I used to know this and it slipped away. I forgot it. How could that be?’

When I was in college, I took the courses that I could in Hinduism, in Taoism, a small seminar from a Chinese professor, and when I was in grad school I read every text that I could in translation on Buddhism and Eastern thought. We have better texts now, better translations. I took vows about seven years ago in the Soto Zen tradition with a mendicant monk, my friend Claude AnShin Thomas…I love the precepts. I try to live them, but I didn’t take the ceremony until I had a chance to do it with a friend.

You have a 4-year-old grandson. How do you instill a love for reading in kids in the age of Play Station and ESPN?

My daughter, who’s a poet and an installation artist, has read a story to him every night of his life. My grandson enjoys it—all kinds of stories. My daughter and I do a children’s book series together called The Adventures of Emery Jones, Boy Science Wonder. The series is named after my grandson, Emery. We have two books out and a 2016 Emery’s World of Science Calendar. The first book is called Bending Time; the protagonist is a 10-year-old child prodigy, a scientific whiz kid, and he’s black. He has a good friend named Gabby who’s hearing-impaired.

Both of the Emery Jones books are aimed at helping kids, especially kids of color, get excited about STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math). But Gabby is a poet, so the second book has one of my daughter’s poems in it. Because we really want STEAM, not STEM. We want Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math.

My daughter reads Emery lots of other children’s books too. So we’re hoping he will have a literary sensibility early in life. But, you know, the world of kids today is a world of screens, it’s a world of computers and smartphones…We don’t have a literary culture anymore; we have a pop culture based on television and movies. Whenever I read a reference that somebody makes—they could be writing about science or about political affairs—the first comparison they reach for is either a television program or a movie. This is common shared knowledge, right? But not so much with literature.

You have said that you look forward to the day when blacks and whites can leave behind “emotionally draining racial discussions” and that if whites had questions about black life, they could read books written by blacks.

When I was in college, I remember getting invited once by a city official to come to a dinner. I was publishing cartoons then and they wanted me to be part of a conversation about race, which, in the late ’60s was on everybody’s lips. We had a lot of discussions back then, and I think the black writer who did the most to try to open up a dialogue was James Baldwin.

But now, the civil rights movement is 50 years past. If a white American or any other kind of American wants to learn about the black experience, we have a library, a library, of books. So I don’t think you need to be that person Baldwin had to be back in the ’60s…Much of what I learned about black American life was from books, certainly the history. I wasn’t on a slave ship. I don’t know anything about slavery; I was born in 1948. So all that prior history I had to learn through public works of scholarship. And people can take courses, too.

You started out as a cartoonist.

When I was 17, I did my first illustrations for a magic catalogue…I took some samples over, and they gave me some work. That was my very first sale. As a young person, a young artist, I wanted to make that first sale. I wanted to transition into being a professional getting paid for what I do. I still have the first dollar I made; I framed it and have kept it in my house. There were times in my life when I was really broke, and I looked at that dollar…

I just had a message from my friend Tim Kreider, who teaches cartooning to students. Tim really liked the fact that back in the day we didn’t have to be as PC as we are today. He wrote a whole essay on a cartoon I did back in the ’70s for a magazine called Players, which was a black version of Playboy. The essay is on the Internet in Comics Journal, and it’s called “Brighter in Hindsight.”

There were cartoons we used to do back in the ’60s and the ’70s that you could never get away with doing today—and not be torn to pieces by one group or the other. And there was early ’70s comedy—Don Ricles, Richard Pryor—that today’s students in particular would be horrified by. The whole purpose of being a comic artist and a cartoonist is to go to places most people don’t want to go to and find humor there. But a lot of people today don’t want to do that. The reason people respond this way, I think, is because they feel [humor reveals] in many cases a lack of empathy and compassion toward others.

Now that’s an important value that we all share. But people do things that are ironic. Look at Middle Passage. There’s humor in Middle Passage. There’s nothing funny about slavery, but the sailors and some of the other characters can do humorous things. Because we’re human beings, we’re not one-dimensional.

So you’re not one to wear your feelings on your sleeve or take offense too quickly.

No, no, well, as a Buddhist, I don’t even believe in the self. I think it’s a social construct; it’s an illusion. David Hume came to much the same conclusion in his own way. The whole idea of identity, see, that’s a problem. Nobody really thinks deeply at heart about what that is. We have been, since the ’80s, in a period of identity politics. People identify themselves in a particular way that is me versus them, or me different from them. I think that leads to all kinds of cultural problems, problems in literature. I think that’s been a huge problem we still haven’t gotten over yet. Identity politics? I don’t know what that is.

What do you think of Middle Passage today, 26 years after you wrote it?

It’s like one of your children. I say, ‘Oh, it’s grown up now, I guess it’s 26 years old, it’s old enough to vote!’ It’s just amazing that a quarter of a century has gone by that quickly. When I think about it, it seems like yesterday. Now my mind is focused on my next book, which is coming out in December. It’s called The Way of the Writer and it’s about the writing craft.

Photos by Christa Neu

Posted on: