A Water Solution in Nicaragua

Members of Lehigh’s chapter of Engineers Without Borders (EWB) help residents of Cebadilla, Nicaragua, dig a trench where pipes have been laid to carry water from new water tanks to village homes. (Photo courtesy of Gustavo Grinsteins Planchart ’18)

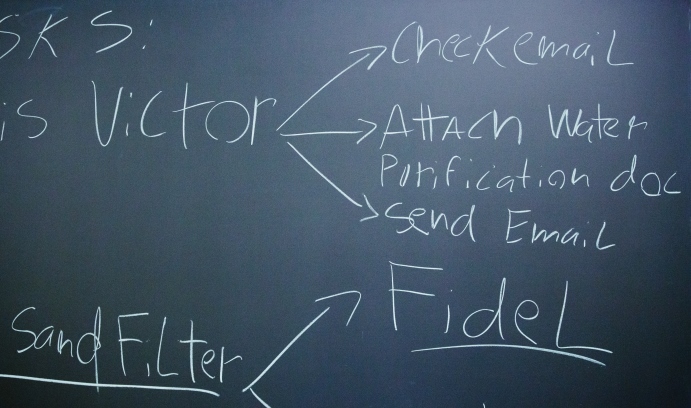

It’s 5 o’clock on a Friday afternoon, and members of the Lehigh student chapter of Engineers Without Borders (EWB) are converging on a classroom in the STEPS building.

The students open their laptops and begin placing phone calls to Cebadilla, a village in southwestern Nicaragua where EWB has helped build a new water-distribution system.

The first call is to Antonia, who works with a Nicaraguan organization called Earth Fund, or Fundación Tierra. Silvia Rosado ’20, a mechanical engineering major, asks Antonia in Spanish about the biosand filters that are being installed in Cebadilla’s homes to purify drinking water.

The EWB students have tested the water from the new distribution system. Now they need to learn how many of Cebadilla’s residents are using and maintaining biosand filters to purify water. The goal is to ensure that the water meets World Health Organization (WHO) standards and to determine if additional treatments are necessary.

Gustavo Grinsteins Planchart ’18, a mechanical engineering major, listens in on Rosado’s conversation with Antonia and suggests follow-up questions. Ana Vargas ’20, a bioengineering major, types rapidly into her laptop.

Rosado asks Antonia where residents are obtaining the sand and the containers for their filters. The sand comes from Managua, Nicaragua’s capital, Antonia says. The containers are sold at the local market.

The call ends and the students translate the conversation into English.

Grinsteins now places a call to Marlene, the students’ primary contact in Cebadilla. Rebecca Luttinen ’20, an international relations and economics major, and Nicole Castillo ’20, an industrial systems and engineering major, take notes.

EWB is considering building a bridge over a small creek in Cebadilla, but it needs buy-in from residents. The bridge could be for pedestrians only or for pedestrians and autos. The community needs to decide which, Grinsteins tells Marlene, and it needs to cover a small portion of the cost.

Before he hangs up, Grinsteins asks Marlene how the new water system is functioning.

“Bien,” she says, “gracias a Dios.”

A receptive community

Cebadilla, a village of about 200 residents and 50-plus homes, is located 15-20 minutes from the tourist town of San Juan del Sur and two hours from Managua.

Until recently, the residents of Cebadilla relied on hand-dug wells for drinking water. But a severe drought caused some wells to dry up, and residents had to truck in water. Runoff from nearby latrines also necessitated a deeper well.

The EWB chapter heard about Cebadilla’s plight three years ago from Earth Fund. The chapter had solved a similar problem in Pueblo Nuevo, Honduras, by helping to build a storage tank and water-distribution system. For its efforts, the chapter received a Davis Projects for Peace prize in 2009.

After careful consideration, the students decided they could have a similar impact on Cebadilla.

“We go through a process before we pick a community to work with,” says Grinsteins, who chairs the EWB translating committee. “The community has to have both the skills and the drive to go ahead with a project—to complete it and then maintain it. Our job is to collaborate with them to accomplish the project.

“The people of Cebadilla have been really receptive. We’ve had good communication with them and have been able to get a lot of things done. We are the organizers but at the end of the day, we’re all working together.”

The Lehigh chapter of EWB has about 50 student members. Many have made week-long trips to Cebadilla to get to know its residents and assess their needs, and then to design the water-distribution system and oversee its construction. The chapter is advised by Kristen Jellison, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering; Richard N. Weisman, professor emeritus of civil and environmental engineering; Daniel Zeroka, an engineering technician in the department; and Mark Orrs, professor of practice in the department of political science and director of Lehigh’s sustainability program.

When EWB members travel to Nicaragua, says chapter president William Kuehne ’17, an IDEAS (Integrated Degree in Engineering, Arts and Sciences) major, “we stay in the community, not in San Juan del Sur. This isn’t a field trip or a touristy thing; it’s serious work.”

In designing the water-distribution system, says Cory Bierman ’17, an environmental engineering major and Cebadilla project manager, EWB worked closely with community residents, including an engineer and technical overseer. Students in a civil and environmental engineering projects class also helped.

In the first phase of the project, the students designed a concrete pad that holds two 10,000-liter water-storage tanks. The Cebadilla mayor’s office drilled a deeper well and installed pumps to move water to the storage tanks. The students designed the system that distributes water from the well to the tank to the village’s homes, and they monitored its installation, both remotely by phone and first-hand in site visits.

In the project’s second phase, the students helped the residents of Cebadilla dig trenches and lay pipe to connect each house in the village to the new system.

Students encountered several design challenges, says Courtney Lenzo ’18, a chemical engineering major. PVC pipe sizes and other specifications differ from Nicaragua to the United States. And head loss, which results from the resistance to flow caused by friction, had to be factored in.

The pumps to the new tanks were installed last August with community help, says Lenzo, who is the EWB chapter secretary. By fall, most houses were connected the tanks. Some houses located further away were not connected until winter, when several EWB students visited Cebadilla.

“This has been a really good experience,” says Grinsteins, who has made three trips to Cebadilla. “I love going there. The best trip was the implementation trip when we did the trenching and piping. Everyone in the community was working on that project.

“We worked on it from the day we arrived until right before the bus came to take us back to the airport. From that point, the community took over the project; we had already finished the main piping to some of the houses.

“It was an amazing trip; we were actually able to accomplish something we had worked a lot of years on.”

A positive impact

Lehigh’s EWB chapter gets most of its funding from the national EWB organization, which receives grants from private corporations and divides them among individual chapters depending on their track records and on the importance of a project. The chapter also solicits donations on its web page, and its fundraising committee writes grant proposals.

EWB requires a regular time commitment outside class. Its five committees—translating, fundraising, social, projects and outreach—meet once a week, as does the executive board. EWB members estimate they spend five to 10 hours a week working for the chapter, and they say the time is well spent.

Bierman found the EWB website before she enrolled at Lehigh and then looked for the chapter at a student club fair the day before classes started her first year at Lehigh.

“EWB is a unique club,” says Bierman. “It’s a chance to do extracurricular activities that will have a positive impact on people, not just for yourself. It’s amazing you can do something like this at a university.”

Carlen Donahue ’17, vice president of the EWB chapter and a materials science and engineering major, joined the group because of her interest in sustainable development.

“The three pillars of sustainable development are economic development and societal and environmental benefits,” says Donahue, who has traveled twice to Cebadilla. “A sustainable development project should focus on at least two of those three.”

Kuehne, who has completed three stints in Cebadilla, says the experience with EWB will further his goal of doing engineering development work after he graduates from Lehigh.

“This is like professional practice for me. At the same time, it’s fun.”

EWB has completed smaller projects for nearby communities, says Kuehne. The repair of a water pump in La Libertad, an hour’s drive from Cebadilla, gave some students the chance to take in the view from one well-situated mountain.

“If you drive to the top of that mountain,” says Kuehne, “you can see Lake Nicaragua on one side and the Pacific Ocean on the other. It’s absolutely beautiful.”

Story by Kurt Pfitzer

Photos by Christa Neu

Posted on: